text by Dorota Babilas

Cats have experienced a considerable growth in status as companion animals and domestic pets since the nineteenth century. Regarded originally as largely untameable creatures, tolerated because of their function as pest control, they have been welcomed into the parlours and praised for their cleanliness, grace, and vivaciousness while retaining some of their wild and mysterious nature. In March 2025, Troy University (Alabama) hosted an online conference on Domestic Cats in Literature that proved a rare treat for cat-loving academics. The topics ranged from Mediaeval cloister cats of Hildegard von Bingen to the recent film Flow, with a special mention of Victorian, and especially Gothic cats. Sidia Fiorato (University of Verona) explored modern retellings of Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire Cat; Sarah Henderson (Robert Gordon University), Debapriya Ganguly (Pune University), Muhammad Metic Çameli (Istanbul University), as well as independent scholars Tiyashi Roy, and Priyanka Dash all investigated various aspects of Edgar Allan Poe’s “Black Cat”. There were two entries on T. S. Eliot’s Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats – my own contribution on the motif of Gothic return in the musical Cats, and Scott Ennis’s poetic re-imagination of the original poem cycle in the form of sonnets.

T. S Eliot’s poem cycle on “Jellicle Cats” is steeped in memories of Victorian times expressed in street names (such as Victoria Grove) and personal reminiscences of feline characters – the leader of the group, the oldest cat called Old Deuteronomy, has lived since “a long while before Queen Victoria’s accession”, and Gus, the Theatre Cat, recalls his thespian triumphs “in the days when Victoria reigned”. The small volume of comical verse written for his godchildren and published with the poet’s own illustrations in 1939 achieved some popularity as a quirky children’s book and was republished in 1940 with illustrations by Nicholas Bentley. In 1981, the poems were rediscovered and mass-marketed by the ground-breaking musical stage show Cats, a collaboration of composer Andrew Lloyd Webber and lyricists Trevor Nunn and Richard Stilgoe who adapted Eliot’s poems to music (there has been a live recording in 1998). Finally, in 2019, Tom Hooper’s controversial film adaptation of the musical was made, which bombed so badly that it threatened to overshadow the original show’s success.

Eliot’s idea of anthropomorphizing cats was not a novelty in British culture, as can be observed for example in popular late-Victorian graphic art by Louis Wain. Wain’s cats – reproduced in thousands of copies – had expressive faces, wore clothes, and engaged in typical human activities. In a similar manner, Eliot’s cats are not cuddly pets, but a free-spirited, rumbunctious characters threading a thin line between human and animal characteristics, often engaging in riotous brawls among themselves or fighting local dogs.

The 2019 film adaptation of the musical was generally panned by critics. A very theatrical show centered on incredible dancing skills was swamped under a CGI and special effects-heavy movie, and stylized make-ups and costumes were replaced by uncanny-valley effect inducing computer-generated creations. Ensembles emphasizing community aspects of cat life were replaced by solo numbers for celebrity performers. Many of the characters were omitted or profoundly reduced in their presence, and the main cast’s characterization drastically changed for the worse. Some subtle LGBT+ allusions were removed. Frequent theatrical breaking of the fourth wall was omitted – except for the uncomfortable finale, in which Judi Dench as Old Deuteronomy has a long speech directly to the audience, elaborating on the fact that “a cat is not a dog”. Victoria, earlier one of the company kittens, was given more focus as a stand-in for the audience and a newcomer to the Jellicle clan, which gave rise to theories that the whole story is a metaphor for cult grooming. The “Jellicle choice” motif – possibly inadvertently – developed into a sort of death cult akin to Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” but with no overt horror, in which the “journey to the Heaviside Layer” was understood as a veiled symbol for an annual sacrificial execution disguised as a prize.

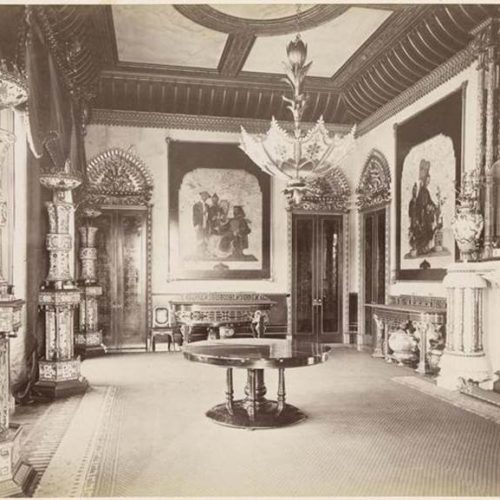

It would be interesting, however, to look at Cats through the lens of Gothic studies. Some of the most recognizable elements of the show are its ominous mood, a moonlit alley (a graveyard in the film), and dissonant music which all work to create an otherworldly atmosphere. Cats themselves are liminal and uncanny creatures, living lives on the margins of human society, but almost devoid of human presence.

The focus of the show is the “Jellicle ball” which is held once a year and during which Old Deuteronomy declares the “Jellicle choice” – the cat who will ascend to the “Heaviside Layer” and be reborn to a new life. The contestants are apparently only some of the cats, and their achievements are usually introduced by other characters. These playfully combine human pursuits (professional work, morality, crime) with recognizable feline traits.

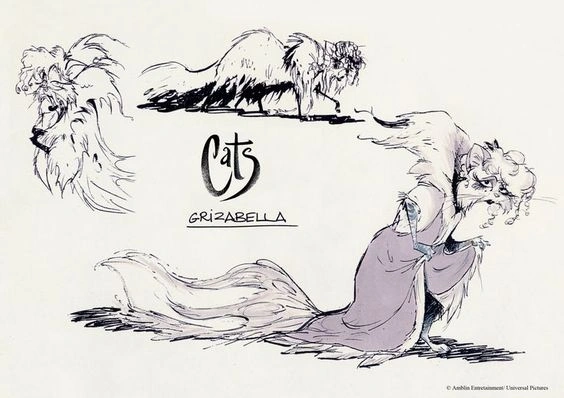

The new song, added to the 2019 movie, referred to “Beautiful Ghosts” and notwithstanding the fact that it was dramatically unnecessary (and even harmful to the plot as it undermined the suffering of Grizabella) it suggested something that might have been present in the musical from the beginning: Are the contestant cats dead already?

The “cat Halloween” recalls the folkloric and literary motif of “Dziady” (Forefathers’ Eve), made famous among others by the dramatic poem of the same title (1823) written by the national bard of Poland, the Romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz. The dramatic poem in four very different parts features wandering ghosts who each lack an important element to the human condition: two small children – suffering, a cruel landowner – compassion, a young maiden – love, a suicidal poet – purpose. The ghosts are raised by a shamanic leader of a rural community during an annual ceremony attended by all villagers. They describe their lives and try to acquire the community’s blessing to pass on to the afterlife. In Cats the prize of a new beginning is given to Grizabella because her story is “not the experience of one life only”, but more universal – a tale of joy, loss, longing, and need for community.

T. S. Eliot’s Cats, reworked and expanded for the stage musical, uses the feline characters as vehicles for light-hearted humor, but also a deeper reflection on the value of happiness, fulfilment, and community. The Gothic motif of wandering ghosts seeking validation of their lives before they can achieve a rebirth, while obviously playing on the superstition of “cats’ nine lives”, is not perceived as threatening or scary, but a celebration of life (human, and perhaps, also animal) whose value reaches beyond an individual experience.

Illustrations: concept art for Old Deuteronomy and Grizabella by Carlos Granger for the aborted animated film of Cats by Amblin Entertainment (1992), https://catsmusical.fandom.com/wiki/Animated_Film