text by Dorota Osińska

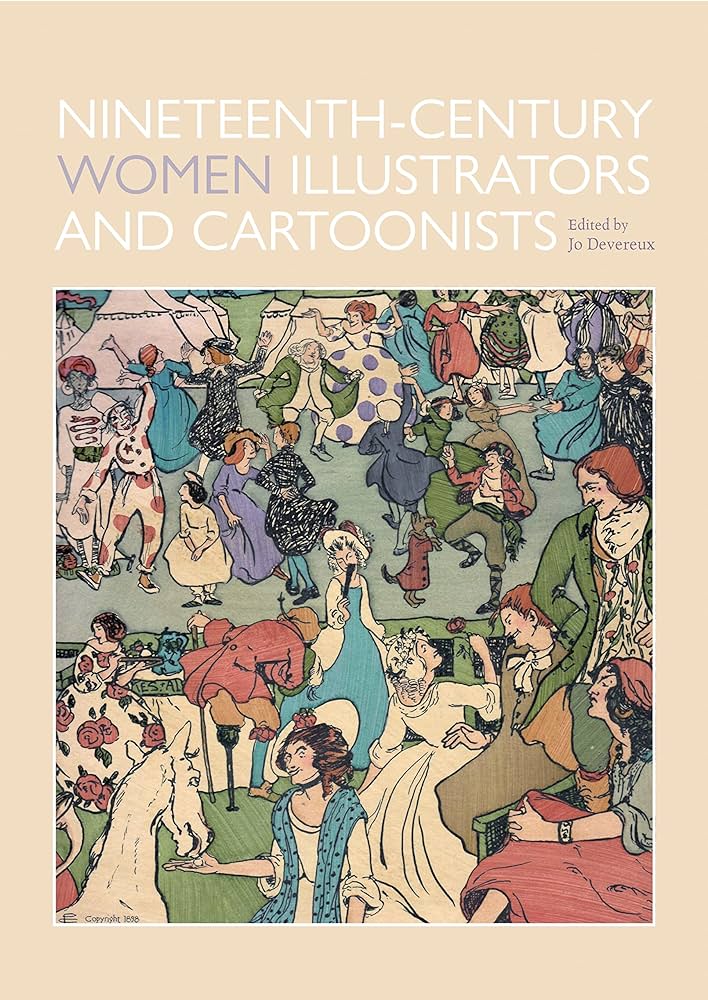

Within the recent scholarship concerning visual arts in nineteenth century Britain, there is a growing interest in the relationship between creativity, economy, and gender. Frequently, this research concerns the Arts and Crafts Movement (and its different manifestations in England, Scotland and Ireland), the Pre-Raphaelites or late-Victorian Aestheticism. In contrast, Nineteenth-Century Women Illustrators and Cartoonists, edited by Joanna Devereux (published by Manchester University Press, 2023) is a provocative attempt to explore the works of fifteen women-artists whose contribution to the development of the illustration has been neglected by the canon. Devereux gathers the renowned scholars in the field of nineteenth century visual culture as well as doctoral students to provide a fresh and captivating take on the women illustrators. In their analyses, the contributors skilfully recognise how the distinctive styles of women-illustrators reflected the peculiarities and richness of creativity throughout nineteenth century art. Admittedly, what should be particularly praised is the wealth of sources. The contributors take advantage of numerous material and digital resources by interspersing pictures, illustrations, diary entries, sketches, journalistic publications with critical essays and electronic databases. Thus, the investigations cleverly acknowledge the modern need for accessibility and extreme usefulness of the Internet sources in the field of literary and cultural studies.

The collection is organised in a neat and easy-to-follow structure which allows for a panoramic view on the topic. Firstly, the author introduces the life of the illustrator, her economic and racial background, education, and the publishing career. Secondly, the chapter focuses on general trends in the oeuvre of a given artist and provides a close analysis of the given work. A potential peril of that structure may be its repetitiveness as each chapter looks almost the same. However, the analysed figures are rather obscure, therefore a clear structure familiarises the reader with the illustrator and shows that the particular artist, despite being now-forgotten, participated in the industry on her own terms. This pattern appears rather stable apart from chapter nine (“Marie Duval: the methods and politics of attribution”) in which the authors decide to include a criticism of the methodological tools included in the previous research on visual arts of Marie Duval. The section of that chapter, “The methodological framework of attribution,” constitutes a fascinating record of the scholarly explorations, how diverse the approaches to the sources are, and what decisions are made by the researchers in the course of study. Despite the fact that the subchapter offers a glimpse into the academic process, it appears rather displaced in the light of the whole work. Potentially, it may confuse the reader since the earlier chapters are mostly centred on content, not on method.

The introduction clearly puts forward the aim of the study, stating that “the book foregrounds the ways in which women illustrators challenged the predominance of male artists by expressing different, often subversive, perspectives, thereby profoundly altering the style and scope of illustration” (2). Although the objective of the book may appear feminist to the core, the authors do not argue for certain interpretations but present a general trend in women’s illustration and come into dialogue with the existing cultural criticism. Of course, the elements of the feminist criticism permeate the book but they are applied critically and as companions to the analytical close reading of the illustrations. The authors take into consideration not only gender but also class. In fact, this aspect is rightly pronounced in the book, highlighting the fact that without social connections and the middle-class or upper-class education, these women would not have been able to publish their works. The topic of race is only mentioned once in the case of Pamela Colman Smith since she is the only artist who is a person of colour. As stated in the introduction, the works of women artists of colour deserve more scholarly attention and should be explored separately (5). Through acknowledging the criteria for selection, the contributors emphasise that their studies point out a variety of themes included in the illustrations within particular gendered and economic contexts.

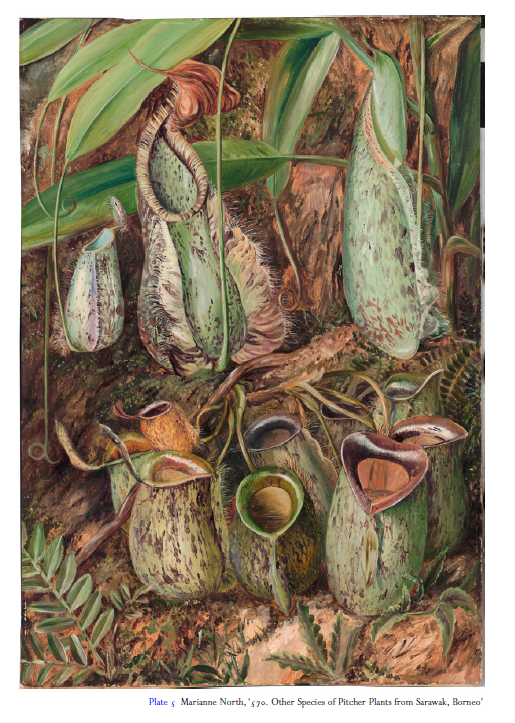

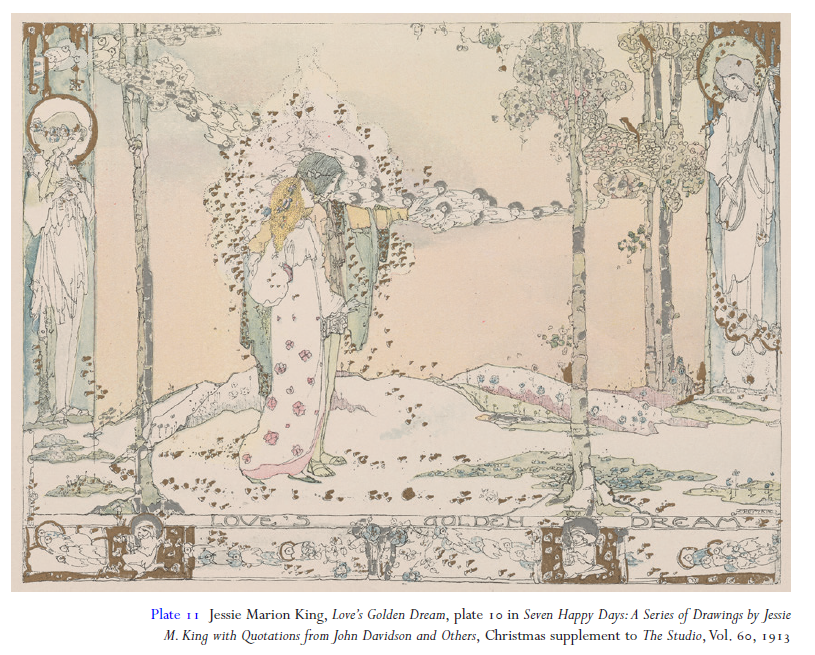

Although each chapter tells the story of a different illustrator, the edition is divided into thematic and chronological sections. These include botany, scientific illustrations, caricatures, children’s books, late nineteenth-century Aestheticism and Arts and Crafts Movement. Such a stimulating assortment of tropes reveals a great proliferation of women’s creativity in nineteenth-century illustration and cartoon industries. Truly, the authors skilfully substantiate that balancing act between social or economic criticism and women’s creativity. In terms of natural history, women illustrators demonstrated a profound interest in botany and zoology, proving that these fields were not exclusive for men and that women developed their own approaches towards these topics. What is more, in the context of children’s literature and caricature, women-illustrators were second to none, criticising society through visual arts available everywhere, without harming their reputation. Finally, the last part of the book that addresses Aestheticism, Art Nouveau, and the Arts and Crafts Movement displays a thought-provoking dynamic between rebellion against the established order and making their own way through the industry. Consequently, the book can be read either in its entirety or dipped into particular chapters. Surprisingly, the collection finishes somewhat abruptly and without any concluding remarks from the editor. Conversely, ending the book with the potential implications for the studying of nineteenth-century illustration and womanhood would show the continuity and disruptions in the tradition of visual arts and women’s participation in creative industry.

Overall, Nineteenth-Century Women Illustrators and Cartoonists presents the empowering side of women’s illustration and dispels the lingering notions about women’s lack of participation in the history of illustration. As the authors discuss, women artists in the nineteenth century should not be treated as victims but as the new participants in the male-dominated business. In fact, Devereux indicates that women illustrators “were not radical feminists; neither were they patriarchal apologists. Instead, they worked within the system to effect change” (15). That approach of compassionate, methodical, and non-vilifying research reverberates in the collection – the contributors carefully and thoroughly explore the grey area between femininity and masculinity, between domesticity and entrepreneurship, between resistance and subversion. Above all, Devereux and the contributors rediscover and properly celebrate the variety of women’s representation, simultaneously admitting that the topic, due to its complexity, still requires further investigation.

Nineteenth-Century Women Illustrators And Cartoonists, edited by Joanna Devereux. Manchester University Press, 2023.