Working with young people and students has taught me that I need to be up-to-date with the latest technologies and I cannot escape it. During our classes at university, names such as ChatGPT, Perplexity or DeepL keep popping up and while some students are absolutely delighted by the prospect of using these tools, others are utterly horrified. Some claim that writing a prompt for ChatGPT is an art itself and creating a good one saves one’s time and energy so you have time to do some more in-depth work. The majority of them, however, are quite suspicious, even guarded, limiting themselves to using it to check what response they get, just for the sake of curiosity. It is fascinating to look at the whole process of deciding whether the information given by AI is actually valid or not.

Apart from being an ECR (Early Career Researcher), I also work as a language instructor. During a series of classes during which students had to research some topics that they had no idea about, the first instinct was to ask ChatGPT for some ideas. Some of them were decent and some just plain silly, so I asked students to look at them critically. At first, they were staring at these responses quizzically, but soon the spark of critical thinking was ignited. Despite them being deeply immersed in the AI world, it was such a lovely thing to observe that they still retain a sense of criticism, suspicion, and caution against the information they were fed. In a different context, I asked students to do some research and look at sources for their essays and projects. The first instinct was to use Perplexity, an AI tool that gives you sources for a passage of text. I asked students to calibrate the settings and see what results they got. In the end, they turned out disappointing (to say the least), with no credible sources, and a very limited number of books or articles. Luckily, they noticed themselves that even though these tools may be used in interesting ways, you should not trust them fully.

However, at the same time, I realised that writing essays and giving feedback on them would be changed forever. Serena Trowbridge, in her excellent rant on Substack writes: “Plagiarism seems retro now: the lure of asking AI to help write your essay must be hard to resist, and yet it does seem to stifle independent thought, and restrict learning opportunities for university students” (Trowbridge). Similarly, Peter Scarfe comments that

AI detection is very unlike plagiarism, where you can confirm the copied text. As a result, in a situation where you suspect the use of AI, it is near impossible to prove, regardless of the percentage AI that your AI detector says (if you use one). This is coupled with not wanting to falsely accuse students. (Goodier)

In fact, I noticed during in-class poem analyses (which may be a challenging reading), the first reaction was to write a prompt and see the interpretation done by algorithms, not a person. Unfortunately, the tendency was to use that interpretation in the essay fully generated by AI.

I was toying with the idea of using AI at the initial stages of research. Gathering ideas, inspirations, reading and doing the digging can be really time-consuming, almost a drag. Recently, I have been interested in biblical stories and their revisions, so I wanted to see what kind of information ChatGPT was going to give me. It was disappointing, borderline dangerous due to AI hallucinations (giving misleading or non-existent information). My prompt was: “Can you find the works of Victorian women poets who were interested in retellings of biblical stories, particularly in the Old Testament”. ChatGPT mentioned some names –Greenwell, Rossetti, Barrett Browning, Pfeiffer, all fine. It gave me some vague ideas on the topic, nothing too in-depth. However, when I started to ask about particular works of Emily Pfeiffer, it gave me a title which did not exist. Since a quick online search showed nothing, I concluded that ChatGPT must have made that up. In response to my query, it responded: “This was an error, and I apologize for the confusion” (“Find the works of Victorian women poets…”) Being familiar with Pfeiffer’s works, I found it amusing, but it may be less amusing for those who did not read anything by her and would not tell fact from fiction.

The use of AI may be potentially dangerous in terms of intellectual property, too. In 2024, Taylor & Francis sold access to its authors’ research as part of an Artificial Intelligence (AI) partnership with Microsoft (Battersby). Human writing was used to train AI, without acknowledging the authors. As Serena Trowbridge recalls the discussion during a conference, “there were discussions about whether we need to be making our research available online and scrape-able because AI is the future so [at least, on a positive note] we might as well help it to get things right” (Trowbridge).

Of course, AI may be a neat and convenient tool, for example, in cancer screening tests (“Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Cancer”) or automated tasks but shouldn’t pose a threat to our creativity. One of the internet memes hit the nail on the head saying “I want AI to do the dishes while I write and draw, not the other way round” (Maciejewska), which, disguised in dark humour, shows that this presence of AI is contested. Fortunately, as I have noticed among my students, there is a healthy scepticism – they use AI, but they do not solely rely on it. They do realise that it is not a magical instrument but an algorithm, which though handy, remains fundamentally unreliable.

Works Cited

“Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Cancer.” National Cancer Institute, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 30 May 2024, www.cancer.gov/research/infrastructure/artificial-intelligence. Accessed 3 July 2025.

Battersby, Matilda. “Academic Authors Shocked after Taylor & Francis Sells Access to Their Research to Microsoft AI.” The Bookseller, 19 July 2024, www.thebookseller.com/news/academic-authors-shocked-after-taylor–francis-sells-access-to-their-research-to-microsoft-ai. Accessed 3 July 2025.

“Find the works of Victorian women poets who were interested in retellings of biblical stories, particularly in Old Testament” follow-up prompts to list sources. ChatGPT, May 13 version, OpenAI, 7 Feb. 2025, chat.openai.com/chat.

Goodier, Michael. “Revealed: Thousands of UK university students caught cheating using AI.” The Guardian, 15 June 2025, www.theguardian.com/education/2025/jun/15/thousands-of-uk-university-students-caught-cheating-using-ai-artificial-intelligence-survey. Accessed 3 July 2025.

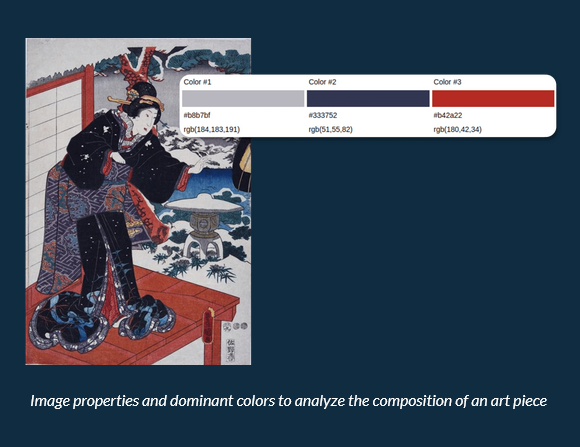

“How Can AI Contribute to Art Historical Analysis and Research?” Eden AI, www.edenai.co/post/how-can-ai-contribute-to-art-historical-analysis-and-research. Accessed 3 July 2025.

Maciejewska, Joanna [@AuthorJMac]. “I want AI to do my laundry and dishes so that I can do art and writing, not for AI to do my art and writing so that I can do my laundry and dishes.” X (formerly Twitter), 29 March 2024, x.com/AuthorJMac/status/1773679197631701238. Accessed 3 July 2025.

Trowbridge, Serena. “AI, Writing and Research.” Substack, 3 June 2025, serenatrowbridge.substack.com/p/ai-writing-and-research. Accessed 3 July 2025.