text by Monika Coghen

… for true words are things,

And dying men’s are things which long outlive,

And oftentimes avenge them …

Byron, Marino Faliero, act V, sc. I, 162-164

In one of his last poems “January 22nd, Missolonghi. On This Day I Complete My Thirty-Sixth Year,” Byron memorably expressed a desire for a soldier’s death. Some would say that he had actually come to Greece to seek it:

If thou regret’st thy Youth, why live?

The land of honourable Death

Is here:—up to the Field, and give

Away thy breath!

Seek out—less often sought than found—

A Soldier’s Grave, for thee the best;

Then look around, and choose thy Ground,

And take thy rest.

On 19 April 1824, he died in Missolonghi after several weeks of lingering illness. The ultimate cause of his death was probably excessive bleeding by his physicians, not a very glorious kind of death. Yet, it awarded him a heroic status, as witnessed in the 1826 painting by Joseph Denis Odevaere, which displays the subtly lit body of the poet with a laurel wreath on his head. His loosely fallen left hand still embraces a lyre and a scroll of paper, and a sword lies by his side. The Greek inscription under the statue over his head reads “Freedom.”

For Odevaere, like for many others in post-Napoleonic Europe who felt that they lived under tyrannical regimes, Byron’s name became synonymous with poetic championship of freedom. Not only did he condemn all forms of tyranny, but he died while organizing military support for Greek insurgents. That was the model some Polish Romantic poets felt they should follow. This was certainly the case with Adam Mickiewicz, who idealized Byron in his prose writings and himself died of cholera in Constantinople while organizing Polish troops to fight at the side of the Ottoman Empire against Russia in the Crimean War.

For Mickiewicz,

Byron opens an era of new poetry; he had been the first to make people feel the whole solemnity of poetry; people saw that one must live the way one wrote, that desires and words were not enough. They had seen the rich poet, educated in an aristocratic country, leave his homeland to fight for the Greek cause. Byron’s great poetic achievement consists in his deep need to turn his whole life into poetry, and thus to narrow the gap between the ideal and the real.[1]

Anyone familiar with Byron’s life will immediately notice that Mickiewicz gets the facts wrong: Byron did not leave England in 1816 to fight for Greek independence, but to escape the consequences surrounding the break-up of his marriage. Mickiewicz completely obliterates all the aspects of Byron’s life and works that led to his “scandalous celebrity”, to borrow Clara Tuite’s phrase.[2] Yet, the Polish poet clearly perceives an essential aspect of Byron’s personality – he was above all a man of action, instantaneously responding to the world around him, ready to take the side of the underdog, be it Nottingham weavers, Irish Catholics, or oppressed nations.

And it is above all as a poet who turned his words into action that Byron appealed to generations of Polish readers, including his editor and translator in Communist Poland, Juliusz Żuławski. Żuławski started publishing Byron’s Selected Writings (Z pism Byrona) in 1953, the year of Stalin’s death. The edition consisted of 4 volumes: Don Juan (4 consecutive editions 1953, 1954, 1955, 1959), Poems and Tales ( Wiersze i poematy, 1954, 1961), Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. Dramas (Wędrówki Childe Harolda. Dramaty, 1955) and Letters and Journals (Listy i pamiętniki, 1960). His final three-volume edition of Byron’s Selected Works (Wybór dzieł) was published in 1986. This edition has remained the standard Polish edition of Byron’s works for the last forty years. In his anthology, Żuławski predominantly uses Polish nineteenth-century translations of Byron, adding to them translations of works hitherto unavailable in Polish, such as The Curse of Minerva, The Vision of Judgment, The Age of Bronze and several lyrics by himself and his contemporaries. Thus, as he acknowledges, his edition is an anthology of the history of translation. Żuławski also published a book on Byron, Byron unposed (Byron nieupozowany), interweaving Byron’s biography with excerpts from his letters and diaries, which went through three editions (1964, 1966, 1979).

In his 1992 memoirs, Żuławski stated that the Polish reception of Byron was primarily political, stimulating generations of Polish writers to active literary [and I would add, not only literary] engagement in political and military struggles. “Admittedly, nowadays some say,” he wrote, “that in a determined situation such fight was and is unnecessary. I don’t envy them their ennui.”[3] Żuławski refers here to the ongoing revaluation of Polish Romanticism, particularly of the glorification of sacrifice for national independence, started in the 1990s by Polish literary scholar Maria Janion. Nonchalantly and with a touch of Byron’s irony, he places himself in the Romantic tradition. This is unsurprising, given Zulawski’s biography. He served as a soldier in the 1939 Polish September Campaign. His father – novelist, poet, and philosopher Jerzy Żuławski – had died a Byronic death, contracting typhoid as a soldier in the Polish Legiony, military troops organized by Józef Piłsudski to fight for Polish independence during World War I.

The problem with Żuławski’s anthology is that through its use of historical translations it may feel dated, and in spite of new translations of satirical verse, it does not do justice to Byron’s mobility. This concept was defined by Byron in Canto XVI of Don Juan as “an excessive susceptibility of immediate impressions—at the same time without losing the past,” and it has proven useful in accounting for constant shifts in his poetic mood – from reflective musings to bitter satire. It is worth noting what Żuławski excludes from his anthology. One of the important omissions is Byron’s poem usually titled “Stanzas”, which he suggested as his ironic epitaph, should he perish in the anticipated Italian uprising against the Austrians in November 1820, included in a letter to Thomas Moore:

When a man hath no freedom to fight for at home,

Let him combat for that of his neighbours;

Let him think of the glories of Greece and of Rome,

And get knocked on the head for his labours.

To do good to Mankind is the chivalrous plan,

And is always as nobly requited;

Then battle for Freedom wherever you can,

And, if not shot or hanged, you’ll get knighted.

The only Polish translation of these lines that I know of was published by Sławomir Mrożek in 1955, and Żuławski was aware of its existence, as he mentions Mrożek’s translations in his list of Polish translations in the introduction to his 1986 edition. It seems that the irreverent, bitterly ironic tone in which Byron deals with the prospective death of freedom fighters, including his own, did not appeal to him and did not correspond to his vision of the poet. After all, the consequences of “the battle for Freedom” that the speaker foresees are either inglorious death or knighthood, the latter condescendingly ironic as he himself is an aristocrat.

For Żuławski, the lines which irrevocably entered Polish literature are Byron’s verses on Greece from The Giaour in Mickiewicz’s translation:

For Freedom’s battle once begun,

Bequeathed by bleeding Sire to Son,

Though baffled oft is ever won.

As though to confirm his claim, Mickiewicz’s translation of these lines appeared on the gates of the Gdańsk shipyard in August 1980 in support of the striking workers.[4]

Byron’s ambivalent poems on the consequences of struggle for freedom sound strangely topical again at the time of the war in Ukraine when poets have joined the ranks of soldiers. One of them was Maksym Kryvtsov, who died on the front line on 7 January 2024, shortly after publishing his award-winning volume Poems from the Battlefield. Kryvtsov had apparently joked to a friend that only if he died on the front, he’d become a classic author. [5] His words may have been prophetic. Death of a poet gives a new dimension to his texts as was the case of Byron.

Monika Coghen is preparing a book on the reception of Byron in Poland and is currently working on Juliusz Żuławski’s editions of Byron.

[1] Adam Mickiewicz, Literatura słowiańska. Kurs trzeci, Dzieła. Wydanie rocznicowe, Warszawa: Czytelnik, vol. 11, p. 33 [trans. M.C.]

[2] See Clara Tuite, Byron and Scandalous Celebrity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

[3] Juliusz Żuławski, Z domu, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 2016, p. 451 [trans. M.C].

[4] On the history of the quotation at the Gdańsk shipyard, see Mirosława Modrzewska, “The Story of a Quote from The Giaour,” in Schoina, Maria, and Nic Panagopoulos, The Place of Lord Byron in World History : Studies in His Life, Writings, and Influence: Selected Papers from the 35th International Byron Conference, (Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2012) https://search-1ebscohost-1com-1h9xsv2hg04aa.hps.bj.uj.edu.pl/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=543077&site=eds-live, pp. 13-25.

[5] Amos Chapple, “Machine-Gun Poet: The Work and Untimely Death of Maksym Kryvtsov,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, January 11, 2024. https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-war-poet-maksym-kryvtsov-death/32769907.html. Accessed April 3, 2024.

Fig. 1 Joseph Denis Odevaere, Lord Byron on His Death Bed. Groeningen Museum. 166 cm x 234.5cm

https://www.museabrugge.be/en/collection/work/id/0000_gro0350_i

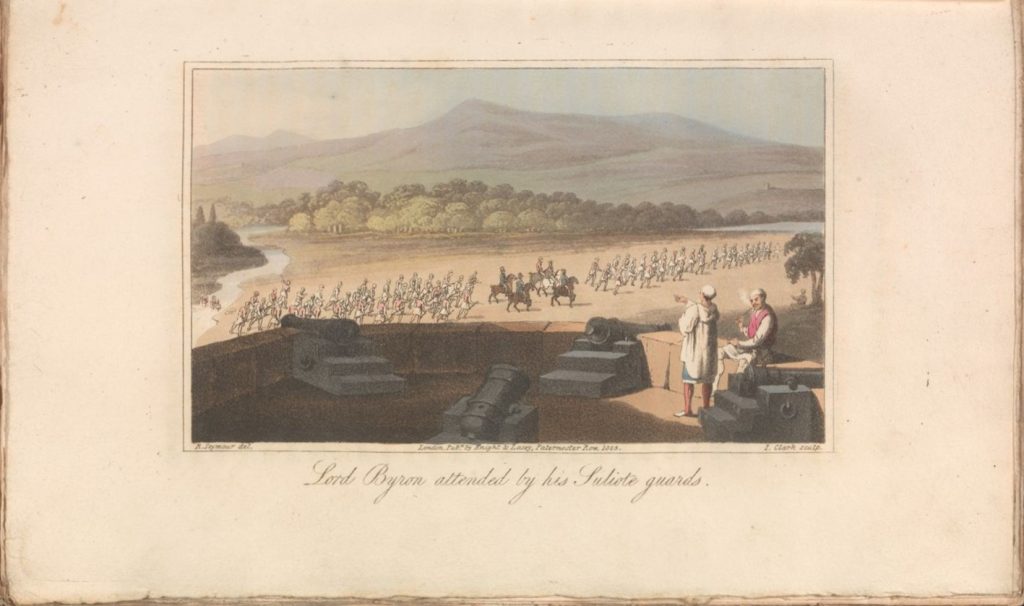

Fig. 2 “Lord Byron attended by his Suliote guards”. Aquatint engraving by J. Clark, after Robert Seymour., in William Parry, The Last Days of Lord Byron: with his lordship’s opinions on various subjects, particularly on the state and prospects of Greece (London : Printed for Knight and Lacey, Paternoster-Row; and Westley and Tyrrell, Dublin, 1825). Yale Center for British Art https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/orbis:3789962