text by Aleksandra Gałązka

Georgius Ultimus

Almost two hundred years ago, on June 26th, 1830, the penultimate monarch of the British House of Hanover died. First the Prince of Wales, then the Regent, and finally King, George IV did not enjoy a good reputation either during his lifetime or posthumously. His excessive self-indulgence, scandalous debauchery, and hatred towards his sickly yet noble father were among the most serious charges which his subjects levelled against him. These general sentiments are aptly summarised in William Thackeray’s satirical book The Four Georges. The author remarks that the monarch “never acted well by Man or Woman” and “left an example for age and for youth to avoid”, sardonically entitling this epitaph to the king in a lofty, mock-classical fashion — Georgius Ultimus (806). Yet Thackeray was still more lenient than the contemporary press. Not long after George IV’s death, The Times published an exceedingly scathing article that stated explicitly:

There never was an individual less regretted by his fellow-creatures than this deceased king. What eye has wept for him? What heart has heaved one throb of unmercenary sorrow? … If he ever had a friend – a devoted friend in any rank of life – we protest that the name of him or her never reached us. (Morison 268)

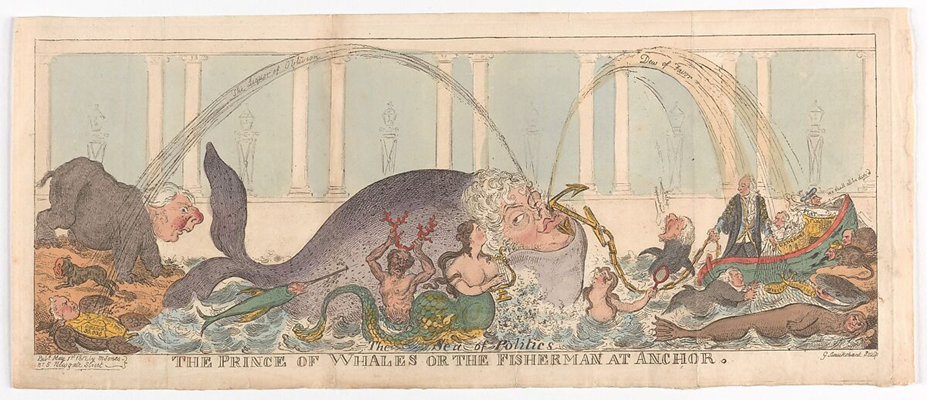

Moreover, the monarch’s life and numerous excesses overlapped with the Golden Age of British satirical caricature. These cartoons – the Regency-era equivalent of hatred-filled social media – were a continuous source of discomfort and humiliation to George, who became one of the cartoonist’s favourite targets. Lucy Worsley notes that “[h]e was brilliant fodder for artists like Gillray, and Cruikshank because of his weight, because of his difficult wife, and because of his endless procession of matronly mistresses” (00:08:17–00:08:28). She also posits that George sometimes even bribed the artists to avoid the most painful indignities (00:08:39–00:08:46). Nevertheless, the monarch’s caricature gallery is as extensive as his lavish lifestyle was. Many of these cartoons are not only amusing but also quite ingenious and artistically refined. One such example is Cruickshank’s The Prince of Whales or The Fisherman at Anchor (see fig. 1), both ridiculing George’s obesity and personal flaws and documenting key aspects of his political and romantic life during the early Regency era.

More recently, however, the perception of George IV has undergone a significant change and he is no longer viewed as a black-and-white figure. The long-standing tendency to vilify him has begun to reverse, with harsh critique and condemnation giving way to more nuanced and sympathetic interpretations. Tim Kirby’s documentary drama The Badness of King George IV (2004) is a prominent example of this shift. Judging by other modern, though somewhat less recent portrayals of George IV, such as The Madness of King George (1994), this reassessment continues to gain strength. Once a mere laughingstock and one of the most despised figures in British royal history, George IV now emerges as the victim of circumstance, shaped by his father’s great ambitions and ideological expectations.

Inspired by Kirby’s evocative production and his empathetic retelling of the king’s life, which offers the ill-famed monarch a measure of redemption, I have chosen to devote this entry to the cinematic vindication of George IV. My aim is to encourage a further reassessment of the stereotypical image of a heartless, self-centred villain who plotted against his father and nearly brought both the monarchy and the kingdom to ruin. The Badness of King George IV serves as the backdrop for the analysis, which focuses on three main aspects: George’s upbringing, his father’s illness, and their remarkably troubled relationship. The first topic to be discussed is the storytelling techniques employed to shed new light on the figure of George IV.

The Ghost of the Reign Past

One of the most striking features of Kirby’s docudrama is its Dickensian ghost-story quality. The film opens with the king spending the final days of his life alone in the bleak chambers of Windsor Castle, haunted by the ghosts of his complex life. He is debilitated by gout and delirious from continually self-medicating with opium to ease the pain the disease inflicts upon him. The drug induces strange dreams, bizarre delusions, and general mental confusion, yet he can’t do without it, as the pain is too severe to endure while sober.

This dreadful condition, along with other echoes of his past, strips away all the splendour he once enjoyed as a young man, the founder and embodiment of the age of elegance and extravagance. The dramatised sequences of the film are set in a luxurious, regal environment, but ironically, the setting lacks all its usual grandeur. The darkness and stillness engulfing the castle create an atmosphere of deep contemplation, gloom, and remorse. George IV, an old sinner who knew no moderation in his lifetime, is now poised to be judged and atone for past misdeeds (Fig. 2).

There is no former business partner to speak in his favour, nor a trio of instructive ghosts offering a chance for redemption. The sole supernatural visitor is a spectre called “The Verdict of History” (see fig. 3), and it has not come to grant the king the final opportunity for change. Instead, the spirit recounts the story of his disgrace, only reinforcing the monarch’s possible pangs of remorse. The director’s approach may appear condemnatory; however, the painful journey into the past that George IV is forced to undertake – much like that of Ebenezer Scrooge – ultimately serves a redemptive purpose. This narrative device, coupled with the king’s pitiful physical and mental condition, succeeds in humanising the monarch in the eyes of the audience. The empathetic portrayal is further reinforced by his occasional flashes of consciousness, during which George delivers emotional counterpleas, one of which closes the film’s introduction and invites the audience to reassess this historically unpopular figure: “There is much of my early life that I now repent, but as king I’ve always tried to benefit my subjects … I have shown mercy to others, and hope that it will be shown to me” (00:04:16–00:04:31).

The Palace of Piety

The roots of George’s so-called “badness” are frequently traced back to his childhood, part of which was spent at Kew Palace – famously nicknamed The Palace of Piety by Horace Walpole. George’s parents, King George III and Queen Charlotte, eschewed sumptuousness and luxury, striving to inculcate similar values of austerity and earthiness into their children. The court was known for scarce decoration, a dull atmosphere, and rigid rules of conduct, especially for the young princes and princesses. As a consequence, the high society tended to give the palace a wide berth. Yet, the same plainness and uprightness that repelled the aristocracy earned George III widespread respect among the quickly emerging and increasingly influential middle class (Babilas 26).

Nevertheless, what might have been admirable from an outsider’s perspective, took its toll on the formation of the royal children, particularly the future king (Smith 18). Many historians highlight the austere and highly regimented nature of George IV’s upbringing, suggesting it had a deleterious impact on his adult life. In her documentary Elegance and Decadence: The Age of the Regency, Lucy Worsley comments on George IV’s extensive self-indulgence proposing it was, in part, a countereffect of his frugal and restrained childhood. Like the commentators in The Badness of King George IV, Worsley offers many convincing examples: the young heir was forced to wear a rigid corset to ensure he would grow up straight and slim; his toys had a strictly educational value; he was denied treats to such an extent that he was not even allowed to eat the crust of a pie tart; and physical punishment was employed for any considered misconduct. Worsley also underscores the ambitious nature of George’s daily schedule: “He had a very strict timetable of lessons. They went on till 8:00 or 8:30 in the evening” (00:04:25–00:04:30). Though all these measures were devised to prepare him for kingship and ensure his success, they conceivably had the opposite effect. The stricter the discipline and the higher the expectations, the more resentful and rebellious George became. These observations closely align with the image of George’s life presented by Kirby. In both cases, the monarch is shown to be deeply oppressed and stifled by his father, whose temper and ideals are starkly at odds with his son’s.

The King’s Madness

Some of the most haunting memories for the titular character in The Badness of King George IV are connected to his father’s episodes of porphyria, which at the time were misinterpreted as manifestations of madness. These bouts were deeply unsettling for the entire court as the king’s brutish behaviour strongly contradicted the values of morality, self-control and rationality that he had, until then, meticulously embodied. The film even suggests that George III’s illness might have been a manifestation of a long-suppressed alter ego, proposing that his extreme virtue and level-headedness were so rigid as to seem unnatural and imposed. According to some preserved accounts, young George was traumatised by his father’s condition and feared that he, too, might one day suffer the same fate:

The king’s madness was enormously embarrassing to George. The father starts talking at an incredibly promiscuous rate, becoming obscene, chasing women around the palace, using that kind of language that was like his sort of innermost buried self-coming out and being uttered – the father, becoming this mad, sexual being all of a sudden. (00:24:14–00:24:39)

George III’s indisposition also reignited the political question of the Prince’s rise to power. The democratic Whig party saw the crisis as a golden opportunity to gain parliamentary dominance and, subsequently, control over the country. As the issue of appointing a regent arose, the anti-monarchist Whigs, led by Charles James Fox, began manipulating the Prince and turning him against his father. George, still young and emotionally volatile, needed little persuasion. He was much annoyed with his father’s authoritarian style of parenthood and had learnt to use politics to retaliate against him long before the Regency Crisis of 1788. Fox used the Prince’s resentment and naivety to undermine both the King and the Tory party. This political manoeuvring exacerbated the already strained father-son relationship and portrayed the Prince as a traitor in the eyes of his family and his subjects. . However, some historical accounts attest that his actions were not as disloyal and disgraceful as they appeared. Kirby’s documentary portrays the Prince as merely a pawn exploited by shrewd and self-serving politicians, who took advantage of his expensive addictions and deep-seated conflict with his father to further their agendas. The Badness of King George IV features excerpts from the Prince’s diary, and one entry in particular reveals the internal conflict young George experienced during his father’s illness: “I tremble at the thought of doing anything which may in the smallest degree endanger the agitating of his majesty’s mind. There is no one both in heart and mind who can be truly all more sincerely devoted and attached to his sacred person than myself” (00:29:23–00:29:41).

From Madness to Badness

While George IV can be seen as a self-oriented and indolent ruler who led a scandalous private life, his personal flaws and public antics should not be examined in isolation. Although The Badness of King George IV neither acquits nor explicitly justifies the monarch’s failings, it opens the door to a more open-minded and multilayered discourse. As the documentary suggests, factors such as the monarch’s highly restricted childhood and the trauma of his father’s illness left a lasting mark on George’s psyche – emotional instability, low self-esteem and a strong urge to assert his independence among them. These, in turn, compelled him to develop some lifelong compensation mechanisms, which indirectly contributed to his tragic downfall – one that today frequently inspires more pity and compassion than the harsh condemnation and ridicule it once did.

Just as porphyria can be interpreted as a reaction to the rigid self-control George III imposed on himself, the strict rules and utopian ideology he enforced upon his eldest son can be seen as decisive factors in George IV’s moral, physical, and mental collapse. The future monarch never managed to meet the impossibly high standards his father set; yet, the fact that none of George III’s children truly did suggests that too much blame may have been placed on the Prince. Paradoxically, in attempting to guard his heir against incontinence and lack of self-regulation, George III may have pushed young George directly into the lion’s den. Despite their many differences, both monarchs appear to have shared a fundamental flaw: a lack of moderation, which contributed to the ill fame of George IV suffered, the decline of the British Hanoverian dynasty, and the broader cultural need to re-evaluate the monarchy itself.

Work Cited

Babilas, Dorota. Wiktoria znaczy zwycięstwo. Kulturowe oblicza brytyjskiej królowej. Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2012.

The Badness of King George IV. Directed by Tim Kirby, Flashback Television, 2004.

Cruickshank, George. The Prince of Whales or The Fisherman at Anchor. 1812, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/393176. Accessed 16 March 2025.

The Madness of King George. Directed by Nicholas Hytner, Channel Four Films, 1994.

Morison, Stanley. The History of the Times: “The Thunderer” in the Making, 1785-1841. London: The Times, 1950.

Smith, E.A. George IV. Yale University Press, 2000.

Thackeray, William Makepeace. Henry Esmond; The English Humorists; The Four Georges. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Worsley, Lucy, presenter. Elegance and Decadence: The Age of the Regency. British Broadcasting Corporation, 2011.