text by Małgorzata Łuczyńska-Hołdys

‘Darkling I listen; and, for many a time, I have been half in love with easeful Death…’

“Ode to a Nightingale”, 51-2

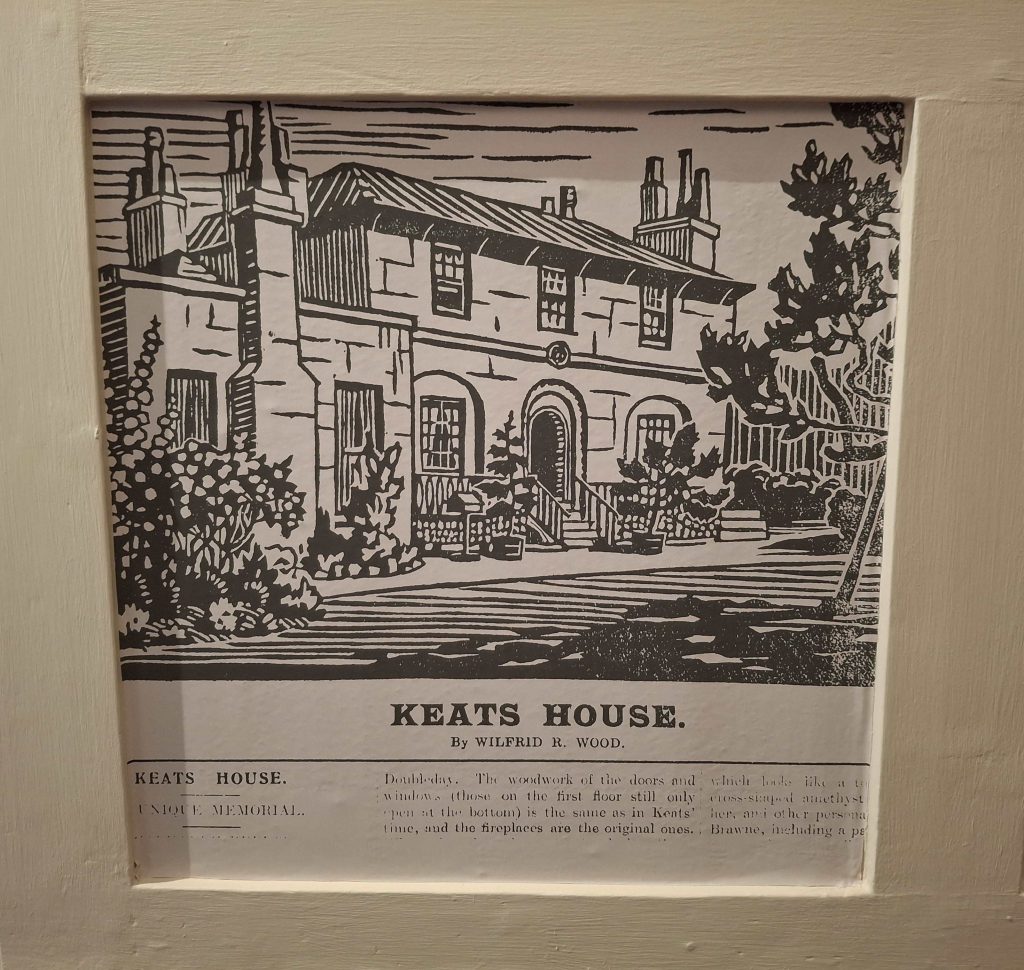

From George Orwell and Daphne de Maurier to Gerald Mainley Hopkins, John Constable, Leigh Hunt, and, naturally, John Keats, Hampstead provided both inspiration and refuge to some of England’s famous artists, poets and writers. Walking through Hampstead, it is impossible not to pause at blue plaques on its houses: allegedly, there are 75 of them. For lovers of Romantic poetry, however, it is the place rich in associations with one poet particularly – John Keats, who spent in Hampstead three years of his short life (Keats died at 25); yet, here he wrote his most memorable poetry, including the famous “Ode to the Nightingale” (he heard the bird’s song in the house’s gardens). To this day, Hampstead continues to honour its link to the poet: beyond the Keats House, there is Keats’s Pharmacy, Keats’s Practice Group, and, on a more humorous note, even Keats Hair.

Keats first came to live in Hampstead in 1817, but it was only in December 1818 that he moved into the dwelling that would become known as Wentworth Place (now Keats House). During his stay there with his friend Charles Brown, Keats became secretly engaged to Fanny Brawne, whose mother rented the west part of the house. The place witnessed the budding of their love affair, as they were divided only by a partition wall. Now, it is the home of the John Keats Foundation and a library, and it hosts annual conferences on the poet’s life and works. This year’s conference theme, “John Keats at Hampstead”, was inspired by the centenary of the house’s public opening as a museum. In 1925, the building faced the threat of demolition to make way for new development. In response, local residents formed the Keats House Memorial Committee, raising funds to purchase and preserve the property. Notable contributors included Thomas Hardy, who donated poems to the fundraising John Keats Memorial Volume, and Keats’s biographer Amy Lowell. The house now celebrates its 100th anniversary with the Keats House 100 exhibition.

As in previous years, the conference was a lively and intellectually stimulating event. It brought together Keats’s researchers – biographers, translators, literary scholars – from all over the world (Great Britain, United States, Greece, Germany, Taiwan, China, Australia, Poland). The topics and methodologies of presented papers ranged from close readings of Keats’s poetry and letters to explorations of the issues of class, colour and sound in his writings and biography. Nicholas Roe (University of St Andrews) presented the results of his research on the origin of a long list of names on the gravestone of Joseph Severn, Keats’s friend and companion, buried alongside the poet in Rome; Greg Kucich (University of Notre Dame) debated the connections between the poetry of Keats and Henry Kirke White; Richard Marggraf-Turley (Aberystwyth University) argued that elements of non-Euclidean geometry may serve as a fine tool for exploring textual space; Eva Jenke (Humboldt-Universität, Berlin) analysed Keats’s treatment of time and space in his poetry; Ou Li (Chinese University of Hong Kong) discussed “Ode to a Nightingale” through the lens of Demodocus’s Songs in Book VIII, The Odyssey.

This year my paper was devoted to the exploration of Keats’s concept of indolence and idleness in relation to his views on poetic creativity. Keats’s letters, along with much of his poetry, reveal an ongoing internal struggle between two distinct ways of approaching life and art. On one side is what he variously refers to as “delicious Indolence” or “abominable Idleness,” a state of leisurely reflection. On the other is a life of focused effort and discipline, which he describes when noting that he “read[s] and write[s] about eight hours a day” (Letters 22). By examining his letters (many of them written from Wentworth Place) and selected poetry dating to the period of his life he spent in Hampstead, I attempted to trace how Keats arrives at his concept of “diligent Indolence” and how this notion intersects with his ideas on sensibility, artistic productivity and intellectual reflection. Keats developed several famous concepts to define his unique model of poetic creativity; they include the idea of the camelion poet; the metaphor of “life as mansion of many apartments”, a receptive stance symbolised by a flower rather than a busy bee; finally, the notion of negative capability. This paper has argued that “delicious diligent Indolence” (Letters 92) belongs to the same category of ideas; Keats’s articulation of this concept marks a milestone in his poetic development; the reconciliation of a life of sensations and, partly, that of thought results in a spectacular outburst of poetic creativity, the outcome of which are the great 1819 poems that we best, know, love and remember.

Works Cited

Scott, Grant F. (ed). Selected Letters of John Keats. Revised Edition. Harvard University Press, 2002.

Keats, John. The Complete Poems, ed. Miriam Allott. New York, Longman, 1970.