text by Magdalena Pypeć

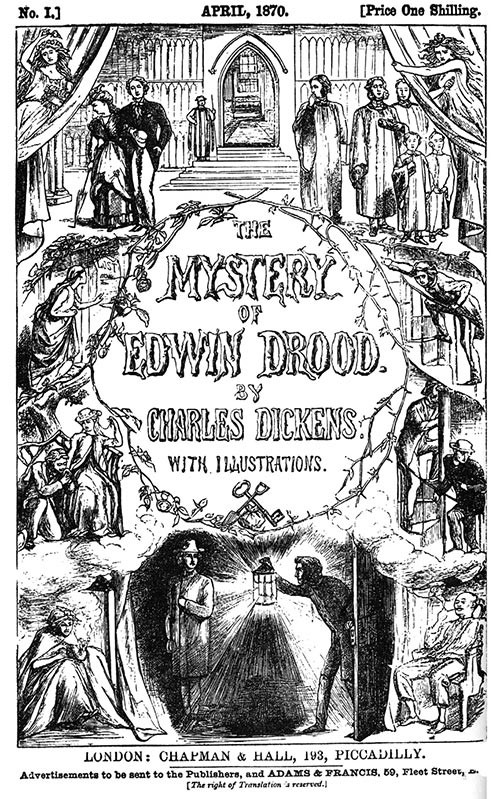

Published at the outset of heightened British imperial activity, The Mystery of Edwin Drood (hereafter referred to as Edwin Drood) contains more colonial references than any other Dickens’s work. All these references situate the “ancient English Cathedral town” from the novel within the larger diverse imperial context and the anxieties that attended British imperial hegemony at this time (7; ch. 1).[1] I would like to suggest reading the novel as a forerunner of imperial Gothic genre discussed by Patrick Brantlinger in his seminal Rule of Darkness. British Literature and Imperialism, 1830–1914. As Brantlinger has pointed out, the three principal themes of imperial Gothic fiction are “individual regression or going native; an invasion of civilisation by the forces of barbarism or demonism; and the diminution of opportunities for adventure and heroism in the modern world” (230). Besides evocations of national regression and images of decline and fall at the time when the empire was at the peak of its power, other hallmarks of the genre include the rhetoric of social Darwinism; images of imperialist rapacity and violence; diabolical twin or demonic doppelgänger; psychological and physical atavism; racial degeneration; insanity (which is how civilisational or psychological degeneration is often interpreted); threatening intruders from the colonies, uncanny objects or malevolent creatures from exotic places invading the metropole; and imagery of pervading darkness and death running throughout the Imperial Gothic fiction. In contrast to early Victorian adventure tales of derring-do (such as Captain Frederic Marryat’s, Robert Michael Ballantyne’s or Thomas Mayne Reid’s novels), imperial Gothic texts are not narratives of triumph, but rather express bathos and disillusionment which frequently accompany the seeming political or economic success of colonial conquests.

Dickens has often been discussed an ardent believer in his nation’s colonial expansion and western civilisation. Brantlinger refers to Dickens’s imperialist sympathies in “The Noble Savage” essay (Household Words 1853), stating that “Dickens’s sympathy for the downtrodden poor at home is reversed abroad, translated into approval of imperial domination” (207). I seek to argue that his last novel offers a reconsideration of imperial ideology, exposes the hypocrisy and corruption of economic and political colonialism, and foreshadows the anxieties symptomatic of imperial Gothic literature flourishing from the 1880s onwards. In the subsequent paragraphs, I discuss how Dickens deploys the trope of the decline of adventure and heroism in his 1870 novel.

At Oxford on 8 February 1870, the newly-appointed pre-Raphaelite art Professor, John Ruskin, delivered his Inaugural Lecture which soon diverted from art to empire, becoming an illustrative example of British enthusiasm for imperial expansion fused with a strong sense of moral duty and glorious heroism of the project. With a similar idealistic message on his lips, justifying his Egyptian ‘civilising’ mission on grounds of moral duty, young Drood in Dickens’s novel is planning “to wake up Egypt a little” by “doing, working, engineering” (ED 71; ch. 8)—especially since the “triumphs of engineering skill … are to change the whole condition of undeveloped country” (ED 31; ch. 3). The potential empire-builder’s words are later reinforced by the patriotic song with which his uncle entertains Cloisterham’s Mayor:

exhorting him (as ‘my brave boys’) to reduce to a smashed condition all other islands but this island, and all continents, peninsulas, isthmuses, promontories, and other geographical forms of land soever, besides sweeping the seas in all directions. In short, he rendered it pretty clear that Providence made a distinct mistake in originating so small a nation of hearts of oak, and so many verminous peoples (ED 127; ch. 12).

The imperialistic message of Edwin’s boast and Jasper’s song can be an implicit reference to boys’ periodical literature which was a clear reflection of contemporary jingoistic ideology. The first boys’ paper of this kind was Boys of England. Issued weekly from 1866 to 1899 by publisher and former Chartist Edwin J. Brett, it achieved enormous success in terms of sales and readership, inspiring other similar publications that shaped their young readers’ attitudes towards British expansionist policies, such as the Boys’ Standard (1875–1892) or the Boy’s Own Paper (1879–1967), (Duane 107). The illustrated periodicals glorified and romanticized the exploits of British empire builders, linking Anglo-Saxonism, manliness, patriotism, and international prestige, as Kelly Boyd explains:

The imperialistic nature of boys’ story papers was a given in their early years. Publishers like E. J. Brett celebrated empire with characters who roamed the globe carrying British ideas and arrogance in their baggage. … The most popular heroes of the Victorian period (1855–1900) were those who left the confines of civilisation to help create and maintain the empire. Sometimes as official representatives of the Queen, but more often as independent men living in far-off climes, they glowed with characteristics of manliness central to the needs of imperial society. They were brave, stalwart and crafty in their dealings with both new terrain and native peoples. They exuded a superiority (if not arrogance) which confirmed England or Britain as the most successful and most virile society in the world. (124–125)

Moulded by such ideology, Edwin’s engineering heroism is quickly undermined by his ironic fiancée, who shrugs off his seemingly patriotic mission with a “Lor!” and “a little laugh of wonder” (ED 31; ch. 3). To Rosa Bud, Egypt appears as Belzoni’s[2] loot displayed for the fee-paying crowd in London exhibitions and the British Museum, which she is forced to study at Miss Twinkleton’s establishment, as she explains disparagingly:

Tiresome old burying-grounds! Isises, and Ibises, and Cheopses, and Pharaohses; who cares about them? And then there was Belzoni or somebody, dragged out by the legs, half-choked with bats and dust. All the girls say serve him right, and hope it hurt him, and wish he had been choked. (ED 31; ch. 3)

Since Edwin juxtaposes primitive Egypt and civilised England, Rosa’s response can be read as an unwitting reminder of the debasement of ancient sacred tombs and temples as a result of colonial actions. Rosa may disparage “Arabs, and Turks, and Fellahs” and Eastern customs but she loves to indulge in oriental goods such as Turkish Delight (ED 30; ch. 3). She is also wooed with “a dazzling enchanted repast” prepared by the widely-travelled Tartar—in which “wonderful macaroons, glittering liqueurs, magically preserved tropical spices, and jellies of celestial tropical fruits, displayed themselves profusely at an instant’s notice” (ED 241; ch. 22). Such images of oriental gains question Edwin’s moral and patriotic visions of his imperial venture for they seem to imply its more obvious goal, honestly and bluntly expressed by one of Jonathan Small’s three Sikh companions in Conan Doyle’s The Sign of The Four: “We only ask you to do that which your countrymen come to this land for. We ask you to be rich”(107).

It is noteworthy that the novel’s deployment of Cloisterham much resembles the stereotypical portrayal of Egypt in imperial discourse and Gothic fiction. “Within the parameters of the Gothic, Egypt is a concept rather than a geographical territory”, as William Hughes explains in Historical Dictionary of Gothic Literature,

Egypt is, in Gothic fiction, a place in which a vague past interacts with an equally vague present. … At the centre of the majority of Gothic narratives set in Egypt, or describing uncanny incidents that center on Egyptian artefacts taken out of the country [to which Rosa explicitly refers], is the issue of life and death. (95–6)

With its mysterious Cathedral crypt, monastic graves, old ruins, local superstitions, and Durdles’s excavations of buried “old ’uns,” the ancient town can equally be described as an “old burying ground”, a marked difference being that, unlike Egyptian mummies, the Cloisterham dead turn to dust upon discovery (ED 41; ch. 4). In fact, Jasper’s and Durdles’s descent into the crypt, and the omnipresence of the dead awaiting “to be stoned and earthed up” (ED 135; ch. 12) bears some resemblance to Belzoni’s account of his exploration of a vault full of decayed Egyptians in the Valley of Tombs of the Kings: “But what a place of rest! surrounded by bodies, by heaps of mummies in all directions” (“The Story of Giovanni Belzoni” 552). Just like the Egypt of Edwin’s imagination, Cloisterham equally seems to be very much in need of “waking up”.

Finally, instead of being crowned (like his fellow engineer Lesseps’s) with a marriage to a beautiful young bride, Edwin’s supposedly heroic mission to Egypt ends with the conversion of adventure into crime, a presumed murder probably committed on the grounds of that holy of hollies—the Cathedral, situated within a convenient train and omnibus travel from the “heart of the civilised world,” as Allan Woodcourt refers to London in Bleak House (560; ch. XLVII).

Works Cited

Boyd, Kelly. Manliness and the Boys’ Story Paper in Britain: A Cultural History, 1855–1940. Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Brantlinger, Patrick. Rule of Darkness. British Literature and Imperialism, 1830–1914. Cornell UP, 1988.

Conan Doyle, Arthur. The Sign of The Four, edited by Christopher Roden, Oxford UP, 1994.

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House, edited by George Ford and Sylvѐre Monod, W. W. Norton & Company, 1977.

—. The Mystery of Edwin Drood, edited by David Paroissien, Penguin Books, 2002.

Duane, Patrick. “Boys’ Literature and Idea of Empire, 1870–1914.” Victorian Studies, vol. 24, no. 1, 1980, pp. 105–121.

Hughes, William. Historical Dictionary of Gothic Literature. Scarecrow Press, 2013.

“The Story of Giovanni Belzoni.” Household Words, 1 March 1851, vol. 2, pp. 548-552. Dickens Journals Online, https://www.djo.org.uk/.

[1] All citations from The Mystery of Edwin Drood come from the following edition which will be henceforth referred to as ED: Charles Dickens, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, edited by David Paroissien. Penguin Books, 2002.

[2] A hydraulic engineer and excavator of the Pyramids, Belzoni published Narrative of the Operations and Recent Discoveries within the Pyramids, Temples, Tombs, and Excavations of Egypt and Nubia in 1820. An article about him was published in Dickens’s Household Words—“The Story of Giovanni Belzoni” (March 1, 1851, vol. 2, pp. 548–552).