text by Konrad Zaręba

Following our recent workshop, WLM: Rising Stars 3, titled “Spectres of Gothic Literature: Reflections, Reworkings, Reinventions”, which featured two presentations focusing on vampire characters, I was struck by the enduring prominence of vampirism in scholarly discourse. Among the variety of Gothic monsters, vampires continue to captivate audiences through their dichotomous nature, blending sexual allure with monstrous characteristics. Interestingly, a comparable dynamic can be observed in the Gothic archetype of reanimated mummies, who similarly embody the tension between fascination and horror. However, unlike vampires, mummies have received considerably less attention in academic exploration. Motivated by this disparity, I have chosen to briefly examine two Victorian narratives that serve as representative works within the mummy subgenre, aiming to shed light on their significance and thematic complexity.

The Rise of Egyptomania

European fascination with ancient Egyptian culture emerged prominently at the turn of 18th and 19th century, sparked by the French invasion of Egypt – a military campaign and occupation of Ottoman-controlled Egyptian territories led by Napoleon during the French Revolutionary Wars. This expedition was significant not only for its military objectives but also for its substantial contributions to scientific and cultural knowledge. Key outcomes included the publication of the monumental Description de l’Égypte (1809-1829) and the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, which laid the foundation for the field of Egyptology. The decryption of hieroglyphs in 1824 by Jean-François Champollion further unlocked access to ancient Egyptian religion, wisdom, and philosophy, fostering an enduring fascination and inspiring centuries of scholarly and popular engagement with Egypt’s rich cultural legacy.

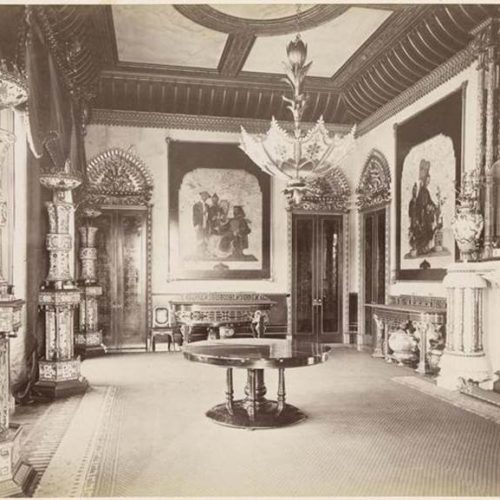

From 1882 until 1956 Egypt was occupied by British forces, a period marked by extensive imperialistic presence and influence in the region. During this time, numerous ancient Egyptian artefacts were removed and transported to Britain, often under exploitative circumstances. Among these artefacts, mummies held particular fascination and became highly sought after. Beyond their historical and cultural significance, mummies were repurposed in ways that reflect the colonial commodification of ancient remains: they were ground into powders for use as pigments in paints and were consumed for their purported medicinal properties. Additionally, mummies featured prominently in the so-called “unwrapping parties”, social gatherings where high society audiences would observe the dramatic and sensationalised unwrapping of mummies’ bandages, further perpetuating their status as objects of spectacle and exploitation.

This period witnessed the emergence of Egyptomania, a widespread fascination with an exoticised and romanticised vision of ancient Egypt. This cultural phenomenon significantly influenced literature, particularly within the Gothic genre. Authors such as Jane Webb (The Mummy! A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century, 1827), Edgar Allan Poe (Some Words with a Mummy, 1845), Arthur Conan Doyle (The Ring of Thoth, 1890, and Lot No. 249, 1892), and Bram Stoker (The Jewel of Seven Stars, 1903) drew upon the Victorian obsession with ancient Egypt and its mummies. These writers creatively reimagined the concept of the reanimated mummy, embedding it within Gothic frameworks to explore themes of the supernatural, the uncanny, and the intersection of ancient and modern worlds.

Both Stoker in The Jewel of Seven Stars and Doyle in Lot No. 249 used the mummy genre to explore the beauty and horror of decay, presenting mummies as paradoxical figures that inhabit a liminal space between life and death – preserved yet deteriorating, mesmerising yet grotesque. These figures symbolise timelessness tainted by decomposition, reflecting the Victorian fascination with ruin and decline and illustrating their anxieties concerning the stability of the imperial system.

The Colonial Other in Lot No. 249

In Gothic literature, two predominant portrayals of the living mummy emerge: the monstrous reanimated corpse, which embodies fears of the colonial “Other” and anxieties regarding imperial decline, and the sexualised, romanticised figure, often female, which reflects Orientalist fantasies and the colonial romanticisation of the East. These dual archetypes position the mummy within Gothic conventions, oscillating between romantic allure and monstrous terror, encapsulating themes of preservation, desire, and the inevitable confrontation with decay. These archetypes are evident in the aesthetic choices of authors, whose descriptive strategies reveal contrasting interpretations of the mummy’s image. While the overarching Gothic aesthetic is a unifying framework, the imagery employed by different authors diverges significantly, illustrating varied engagements with the mummy as both a symbol and a narrative device.

Lot No. 249 by Arthur Conan Doyle recounts the story of Abercrombie Smith, a University of Oxford student who becomes increasingly suspicious of the peculiar events surrounding Edward Bellingham, a fellow student specializing in Egyptology. Bellingham, who possesses a collection of ancient Egyptian artefacts, including a mummy, is at the centre of a series of suspicious occurrences. After observing the mummy inexplicably disappearing and reappearing, coupled with two incidents in which Bellingham’s adversaries are violently attacked, Smith deduces that Bellingham is engaging in the reanimation of the mummy. Doyle vividly describes the mummy:

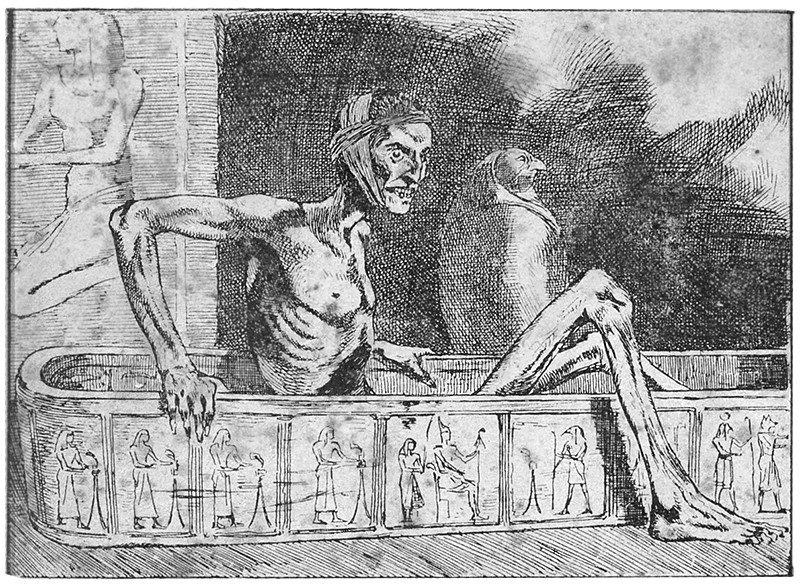

Smith stepped over to the table and looked down with a professional eye at the black and twisted form in front of him. The features, though horribly discoloured, were perfect, and two little nut-like eyes still lurked in the depths of the black, hollow sockets. The blotched skin was drawn tightly from bone to bone, and a tangled wrap of black coarse hair fell over the ears. Two thin teeth, like those of a rat, overlay the shrivelled lower lip. In its crouching position, with bent joints and craned head, there was a suggestion of energy about the horrid thing which made Smith’s gorge rise. The gaunt ribs, with their parchment-like covering, were exposed, and the sunken, leaden-hued abdomen, with the long slit where the embalmer had left his mark; but the lower limbs were wrapped round with coarse yellow bandages. A number of little clove-like pieces of myrrh and of cassia were sprinkled over the body, and lay scattered on the inside of the case. (252-253)

The portrayal of the mummy is deliberately crafted to evoke repulsion and generate negative reactions from the audience. The mummy embodies the central dichotomy of decay and preservation, which lies at the heart of its symbolic significance. As a decayed corpse, it visually represents death and deterioration; however, unlike other rediscovered remains of antiquity, the Egyptian mummy stands out due to the exceptional preservation achieved through the meticulous ancient process of mummification. This duality underscores the liminal nature of the mummy, existing in an intermediate state between decay and preservation. Doyle’s descriptive choices emphasise this unsettling liminality, offering a depiction that is devoid of redeeming qualities and designed to provoke unease, aligning with Gothic conventions of the grotesque.

In this short story, two distinct archetypes emerge when analysed through the lens of postcolonial theory: the colonial “Other”, embodied by the mummy, and the colonizer’s “self”, represented by Abercrombie Smith and Edward Bellingham. The concept of the colonial “Other” reflects the process by which colonial powers construct the identities of colonised peoples as fundamentally different, inferior, and alien. This construction often serves to justify domination and exploitation and is deeply rooted in binary oppositions such as civilised/barbaric and modern/primitive, positioning the colonizer as the superior “self” and the colonised as the subordinate “Other”. Within this framework, the mummy is portrayed as subhuman, embodying degeneration and decay. Despite its ancient origins and transcendence of mortality, it remains subjugated as a servant to its white master, reinforcing colonial hierarchies. The characters in the story –Oxford University students and members of the British upper-class elite – interact with the mummy in three primary ways: as victims, as aggressors seeking its destruction, or as masters exerting control. These patterns mirror colonial narratives that depict the “Other” as a threat to civilised society, one that must be either annihilated or subjugated to ensure the stability and prosperity of the empire.

The Sexualized Mummy in The Jewel of Seven Stars

Bram Stoker’s The Jewel of Seven Stars narrates the story of Malcolm Ross, a young barrister, who is summoned late at night to the home of his friend Margaret. Upon arrival, he discovers that her father has been injured by an unidentified assailant and is in a peculiar, coma-like state. As the investigation unfolds, the characters uncover a connection between a mysterious artefact that Margaret’s father brought back from Egypt, a mummy, and the ancient Egyptian queen Tera. It is revealed that Queen Tera, having transcended death, seeks resurrection in the modern era.

The male gender of Doyle’s mummy is significant in its association with morbid and repulsive imagery, which stands in sharp contrast to Stoker’s depiction of the female mummy. In The Jewel of Seven Stars, Stoker describes the severed hand of the mummy as follows:

Within, on a cushion of cloth of gold as fine as silk, and with the peculiar softness of old gold, rested a mummy hand, so perfect that it startled one to see it. A woman’s hand, fine and long, with slim tapering fingers and nearly as perfect as when it was given to the embalmer thousands of years before. In the embalming it had lost nothing of its beautiful shape; even the wrist seemed to maintain its pliability as the gentle curve lay on the cushion. The skin was of a rich creamy or old ivory colour; a dusky fair skin which suggested heat, but heat in shadow. (72)

In his depiction of a decomposed severed limb, Stoker employs a markedly different convention from that of Doyle. The hand of Stoker’s mummy is portrayed not as repulsive but as strangely seductive and attractive, evoking a sense of sexual allure. This approach aligns closely with Gothic conventions, reminiscent of the portrayal of vampires as simultaneously visually pleasing and erotically charged, despite their undead nature and intrinsic association with death. While vampires are frequently rooted in European cultures and folklore (though one might argue that Stoker’s Dracula leaving Wallachia for London exemplifies a form of “otherness”), the mummy is almost exclusively tied to Egypt, a region situated within the broader orientalised sphere. Stoker’s portrayal of Queen Tera thus represents a contrasting side of the colonial perception of “otherness”. While Doyle’s representation of the mummy aligns with a view of the East as barbaric and monstrous, starkly opposed to the “civilised” West, Stoker’s vision romanticises and even fetishises the mummy, presenting a more complex and ambivalent relationship with the exoticised East. This dynamic is particularly evident in the final chapter of the novel, where Stoker’s characters unwrap Queen Tera’s mummy and encounter an extraordinary sight:

We all stood awed at the beauty of the figure … As he stood back and the whole glorious beauty of the Queen was revealed, I felt a rush of shame sweep over me. It was not right that we should be there, gazing with irreverent eyes on such unclad beauty: it was indecent; it was almost sacrilegious! And yet the white wonder of that beautiful form was something to dream of. It was not like death at all; it was like a statue carven in ivory by the hand of a Praxiteles. There was nothing of that horrible shrinkage which death seems to effect in a moment. There was none of the wrinkled toughness which seems to be a leading characteristic of most mummies. There was not the shrunken attenuation of a body dried in the sand, as I had seen before in museums. All the pores of the body seemed to have been preserved in some wonderful way. The flesh was full and round, as in a living person; and the skin was as smooth as satin. The colour seemed extraordinary. It was like ivory, new ivory …. (177-178)

Orientalist romanticisation or fetishisation refers to the process by which Eastern cultures are idealised, exoticised, and often sexualised through Western perspectives. These portrayals tend to simplify and distort complex societies, reducing them to stereotypical or fantastical images that reflect Western fantasies and biases rather than the lived experiences of the cultures being depicted. In these representations, women from “Oriental” cultures are frequently sexualised, portrayed as hyper-feminine, submissive, or exotic temptresses, while men are often depicted as violent, dangerous, or barbaric. Such stereotypes reinforce colonial hierarchies and gendered power dynamics. While Queen Tera is not relegated to the role of a submissive sexual object in Stoker’s narrative – she is portrayed as a wise and powerful queen, adept in mystical arts and capable of asserting influence even beyond the confines of her physical death – it is evident that her remains are depicted far more favourably than those in Lot No. 249. Additionally, Queen Tera is inextricably connected to Margaret, who serves as a vessel for the queen’s spirit, awaiting resurrection. Margaret’s role as the protagonist’s love interest from the outset firmly situates Queen Tera within the sexualised sphere, both in relation to the protagonist and, by extension, to the readers, given the first-person narration. This dynamic is further reinforced by the description of Queen Tera’s unwrapped mummy, which defies expectations of decay. Rather than appearing as a decayed corpse, she is described as a beautiful woman seemingly asleep. Her nudity, emphasised in the text, underscores the extent to which she is sexualised, even in death, reflecting the intersection of Gothic aesthetics and Orientalist romanticisation.

The Gothic Reanimated Mummy

In conclusion, the Gothic archetype of the reanimated mummy, as portrayed in Doyle’s Lot No. 249 and Stoker’s The Jewel of Seven Stars, offers a rich field of analysis for understanding Victorian anxieties and fascinations. Through contrasting depictions – one rooted in repulsion and colonial fears of the “Other”, and the other imbued with Orientalist romanticisation and eroticism – these narratives reveal the complex intersections of imperialism, gender, and cultural perception. While Doyle’s monstrous mummy underscores themes of decay, subjugation, and the grotesque, Stoker’s Queen Tera reflects a romanticised idealisation of the East, merging beauty and power with an undercurrent of sexualisation. These dual representations not only encapsulate the tension between fascination and horror inherent in Gothic literature but also mirror broader societal preoccupations with empire, race, and the exotic. By placing mummies within such intricate frameworks, these works underscore their thematic relevance and highlight the enduring capacity of Gothic literature to interrogate and reimagine cultural and historical narratives.

Works Cited

Doyle, Arthur Conan. “Lot No. 249”. Return from the Dead: A Collection of Classic Mummy Stories, edited by David Stuart Davies, Wordsworth Editions, 2006, pp. 245–273.

Stoker, Bram. “The Jewel of Seven Stars”. Return from the Dead: A Collection of Classic Mummy Stories, edited by David Stuart Davies, Wordsworth Editions, 2006, pp. 3–187.