text by Konrad Zaręba

In 1893, Oscar Wilde composed the one-act drama Salomé, which retells, as its title indicates, the biblical narrative of Salome and the execution of John the Baptist. Because the play portrays biblical figures, it was prohibited in Britain and did not receive a public performance there until 1931. At the time of its composition, all theatrical works in Britain were required to be licensed by the Lord Chamberlain, whose office refused approval on the grounds of an established ban against staging biblical characters. Wilde himself never witnessed a production of the play: the only performances during his lifetime occurred in 1896, when he was incarcerated for “gross indecency” following his conviction for homosexual activity. Salomé premiered in its original French in a single performance on 11 February 1896 at the Théâtre de la Comédie-Parisienne, with Lina Munte (fig. 1) in the title role. The drama subsequently found considerable success after Richard Strauss used Wilde’s text as the basis for his celebrated 1905 opera Salome. The most influential English version of the play, translated by Wilde’s lover Lord Alfred Douglas and heavily revised by Wilde, appeared in print in 1894, accompanied by Aubrey Beardsley’s now-iconic illustrations in the decadent style.

The play centres on princess Salome, the daughter of Herodias and stepdaughter of King Herod Antipas, who becomes infatuated with Jokanaan (John the Baptist), then held in captivity within the palace. Despite Salome’s attempts to seduce him, Jokanaan, consumed by prophetic and apocalyptic visions, repels her advances. Salome vows that she will kiss him whether he consents or not. Later, Herod, lusting over his stepdaughter, implores her to dance for him. She agrees only on the condition that he grant her whatever she requests. After performing the Dance of the Seven Veils, Salome demands Jokanaan’s head. Though horrified, Herod capitulates, and the prophet is executed. Salome then kisses the severed head, fulfilling her vow. Witnessing this act, Herod, overcome with revulsion and fear, orders his guards to kill her, and she is crushed beneath their shields.

The Dance of the Seven Veils

A pivotal moment in the play, arguably its point of no return, is the well-known Dance of the Seven Veils. Salome’s performance for Herod is rendered so mesmerizing that he becomes willing to satisfy any request she might make, even at personal cost. The nature of this dance, however, remains largely undefined in the biblical sources. The Gospels provide only minimal description: “and when the daughter of the said Herodias came in, and danced, and pleased Herod and them that sat with him, the king said unto the damsel, Ask of me whatsoever thou wilt, and I will give it thee.” (Mark 6:22–23) and “But when Herod’s birthday was kept, the daughter of Herodias danced before them, and pleased Herod. Whereupon he promised with an oath to give her whatsoever she would ask.” (Matthew 14:6–8). Beyond these brief statements, the biblical text offers no further elaboration regarding the circumstances, style, or significance of the dance. It is merely established that the unnamed daughter of Herodias, identified as Salome only later by Flavius Josephus in Antiquitates Iudaicae, performed before Herod in such a manner that it elicited from him a vow to fulfil her request without reservation.

Given the play’s richly ornamented style, full of descriptions of gems, precious stones in Herod’s possession, and white peacocks wandering through his gardens, all characteristic of the late Victorian aesthetic movement, one might expect Oscar Wilde to provide a detailed account of the Dance of the Seven Veils. Yet this expectation is subverted entirely. Wilde writes only: “SALOMÉdances the dance of the seven veils” (737). There are no elaborate descriptions, no decadent embellishments, and no choreographic instructions. Wilde effectively leaves the interpretive burden of the dance to the reader’s imagination, and, in performance, to the creative choices of director and actor. The single piece of information offered, that Salome dances and possesses seven veils, raises additional questions, as even the nature of the veils is undetermined. They may be construed as seven garments, seven head coverings, or even seven curtains within the performance space.

Interpretations of the Dance

Numerous scholars have proposed theories regarding the possible origins and meaning of the Dance of the Seven Veils. Some interpretations situate it within the realm of ritual, drawing on ancient Mesopotamian mythology associated with the goddess Inanna, also known as Ishtar. In a katabatic narrative, Inanna descends into the underworld, removing one article of clothing at each of the seven gates until she stands entirely naked. Jess Sully observes that Archibald Sayce, the Oxford professor of Assyriology, who was acquainted with the Wilde family and corresponded with Oscar Wilde, translated ancient tablets containing this myth, making it plausible that Wilde encountered the material and drew inspiration from it. However, Sully also stresses that despite the interpretive appeal of this theory, there is no concrete evidence to confirm Wilde’s direct engagement with Sayce’s translation or the myth in general (24).

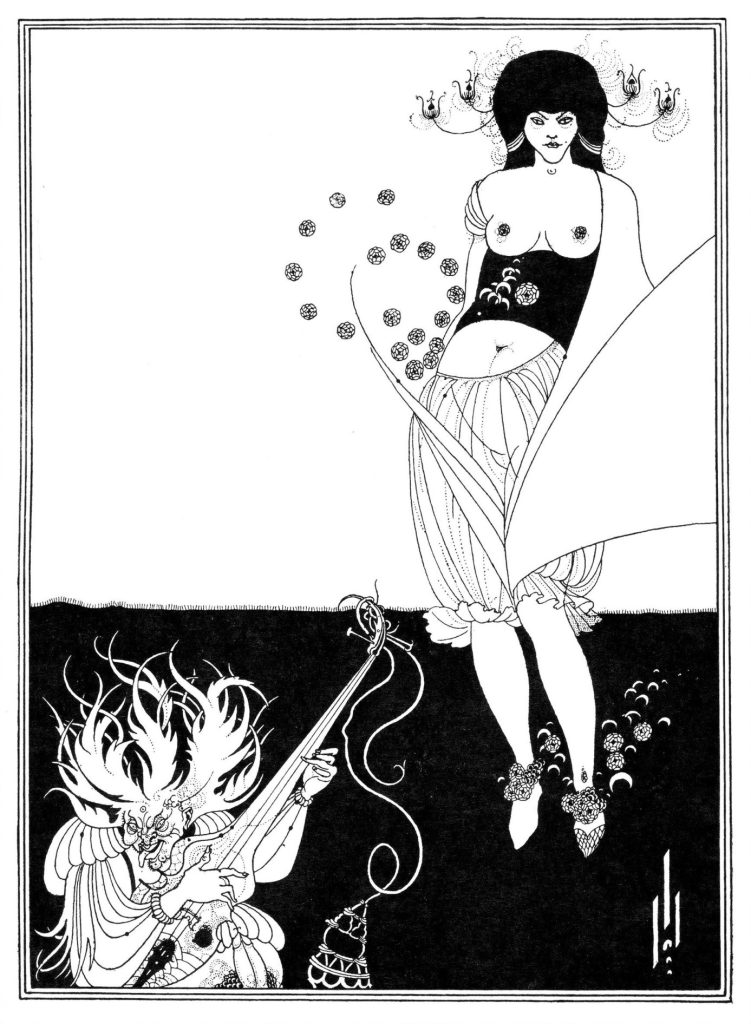

A second, and considerably more firmly grounded, interpretation situates the Dance of the Seven Veils within the domain of orientalist fantasy. In 1893, Wilde inscribed a French edition of Salomé to Aubrey Beardsley with the revealing dedication: “For Aubrey: for the only artist who, besides myself, knows what the dance of the seven veils is, and can see that invisible dance” (Bentley 31). Beardsley subsequently produced illustrations for the British edition, including one titled The Stomach Dance, which depicts Salome in orientalist, Middle Eastern–inspired belly-dancer costume (fig. 2). This visual interpretation strongly suggests that the Dance of the Seven Veils corresponds to a nineteenth-century, highly sexualised and eroticised conception of “Eastern” belly dancing. Such a reading coheres with the Decadent and Aesthetic movements’ broader fascination with orientalism, particularly its investment in sensuality, sexuality, and aestheticized exoticism.

Although Wilde does not specify the nature of the veils or their function within the play, the dance is frequently assumed, and visually represented, as an act of unveiling. Read as a highly erotic performance, Salome’s dance is often interpreted as a form of striptease: she dances for the lustful Tetrarch, gradually revealing one layer (or one veil) after another until she stands naked before him.

Afterlives of Salome

While from a modern point of view Salome might appear to function as a conventional femme fatale, typified by hostile female sexuality deployed against a virtuous man, further heightened by orientalist aesthetics for dramatic effect, there is another dimension to consider. The scandalous and decadent elements of Salomé stood in direct opposition to the prudish norms of Victorian propriety. By foregrounding female desire and corporeality, Wilde’s play and its subsequent interpretations challenged prevailing patriarchal constraints and cultural anxieties surrounding women’s sexual agency. As Toni Bentley writes:

Witnessing Herod’s insistence, Salome has learned the potency of the sword she wields—her own young body. In her ability to display it—and withhold it—lies her power, her only power. This dance was her liberation. Salome became feminist through Wilde, achieving her emancipation by embracing her own exploitation. She grasped her freedom through irony, not tyranny, through manipulation of reality rather than protest about reality (30).

Inspired first by Wilde’s play and later by Strauss’s widely celebrated opera, numerous female performers during the suffrage era appropriated the Dance of the Seven Veils as a celebratory assertion of feminine identity. A notable example is Maud Allan (fig. 3) in The Vision of Salome (1908), whose interpretation “introduced a set of codes for female bodily expression that disrupted the Victorian conventional dichotomies of female virtue and female vice and pushed beyond such dualisms (Walkowitz 345–346).

Allan’s biography presents striking parallels to that of Oscar Wilde. In 1918, Noel Pemberton Billing published an article accusing Allan of being a lesbian and a German collaborator during the First World War. Allan brought a libel suit, and the ensuing trial became a national spectacle. The jury ultimately found Billing not guilty, and the case incited intense public scrutiny of the performance, Wilde’s legacy, and Allan herself. The trial and the accompanying public backlash contributed, among other factors, to the decline of Allan’s career in Europe. The similarities to Wilde’s own legal downfall are notable: in 1895 he sued the Marquess of Queensberry for libel following accusations of sodomy. Like Allan, Wilde lost his case; his professional life was destroyed, and he was subsequently imprisoned.

The indeterminacy at the heart of the Dance of the Seven Veils, its textual elusiveness, mythic resonances, and orientalist re-imaginings has allowed Salome to persist as a uniquely adaptable cultural figure. Wilde’s refusal to describe the dance, far from an omission, becomes a deliberate aesthetic strategy that invites subsequent generations to reframe its meaning. The dance functions as a site where anxieties surrounding sexuality, spectacle, and power converge. This interpretive openness enabled Salome’s transformation from biblical footnote to a symbol of feminine agency, particularly visible in the suffrage period, when performers such as Maud Allan appropriated the dance as an embodied challenge to Victorian binaries of virtue and vice. Its afterlives demonstrate Wilde’s enduring capacity to expose and unsettle the social norms of his era, while continuing to offer fertile ground for feminist, queer, and post-orientalist reassessments today.

Works Cited

Beardlsey, Aubrey. The Stomach Dance. 1894. The Victorian Web. www.victorianweb.org/art/illustration/beardsley/8.html.

Bentley, Toni. Sisters of Salome. Yale University Press, 2002.

The Bible. Authorized King James Version, Oxford University Press, 2008.

Lina Munte as Salome. 1896. Smithsonian Magazine. www.smithsonianmag.com/history/why-oscar-wildes-play-about-a-biblical-temptress-was-banned-from-the-british-stage-for-decades-180986047/.

Maude Allan, a stage dancer. 1923. J. Willis Sayre Collection of Theatrical Photographs, digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/digital/collection/sayre/id/1473/rec/13.

Sully, Jess. “Narcissistic Princess, Rejected Lover, Veiled Priestess, Virtuous Virgin: How Oscar Wilde Imagined Salomé”. The Wildean, no. 25, 2004, pp. 16-33.

Walkowitz, Judith R. “The ‘Vision of Salome’: Cosmopolitanism and Erotic Dancing in Central London, 1908-1918”. The American Historical Review, vol. 108, no. 2, 2003, pp. 337-376.

Wilde, Oscar. “Salomé: A Tragedy in One Act”. Collected Works of Oscar Wilde, translated by Lord Alfred Douglas, The Wordsworth Editions, 2007, pp. 719-742.