text by Magdalena Pypeć

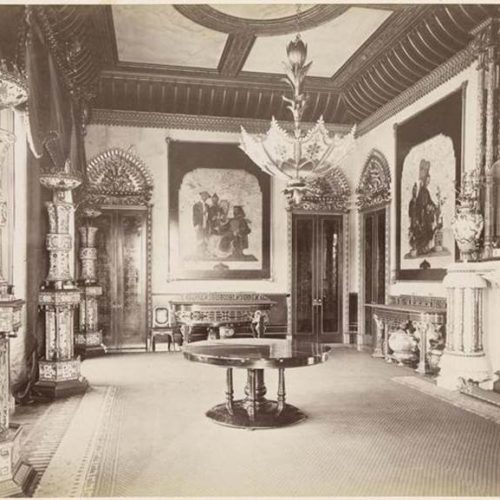

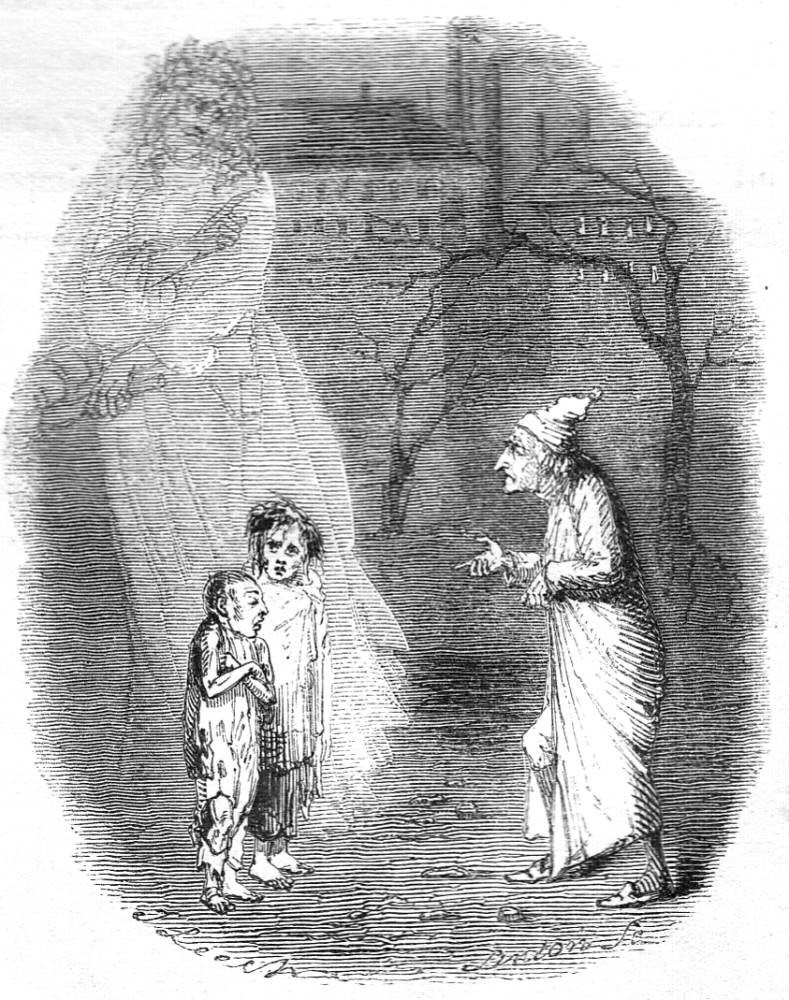

One of the pressing social issues that deeply concerned Charles Dickens was the need for universal education and comprehensive sanitary reform, both of which he deemed essential to improving the lives of the poor. In Dickens’s view, these two causes were inextricably linked. This connection is vividly illustrated in A Christmas Carol, where the Ghost of Christmas Present reveals to Scrooge two wretched child-monsters, Ignorance and Want (see Figure 1). The ghost issues a grim warning: “most of all beware this boy [Ignorance], for on his brow I see that written which is Doom, unless the writing be erased” (Stave III). The inspiration for this scene came from Dickens’s visit to the Field Lane Ragged School, a charitable institution providing free education to destitute children of the impoverished 19th-century working class (see Figure 2). In a letter dated 16 September 1843 to Angela Burdett-Coutts—a philanthropist and one of England’s wealthiest women—Dickens recorded his impressions of the dire conditions at the school, drawing a clear connection between squalor and educational neglect:

I have very seldom seen, in all the strange and dreadful things I have seen in London and elsewhere, anything so shocking as the dire neglect of soul and body exhibited in these children. And although I know; and am as sure as it is possible for one to be of anything which has not happened; that in the prodigious misery and ignorance of the swarming masses of mankind in England, the seeds of its certain ruin are sown, I never saw that Truth so staring out in hopeless characters, as it does from the walls of this place. (Letters, vol. 3)

Dickens firmly believed that sanitation must be addressed before education could succeed. In a letter dated 3 January 1854 to Arthur Helps—writer and advisor to Queen Victoria—he emphatically reiterated this stance: “Sanitary improvements are the only thing needful to begin with; – and until they are thoroughly, efficiently, uncompromisingly made (and every bestial little prejudice and supposed interest contrariwise, crushed under foot) even Education itself will fall short of its uses” (Letters, vol. 7).

It appears that Dickens had a keen eye for good sanitary conditions wherever he travelled. This is exemplified by his account of his first visit to Boston and its surroundings during his 1842 American tour. One of the first observations he makes at the Perkins Institution and Massachusetts Asylum for the Blind is that “[g]ood order, cleanliness, and comfort, pervaded every corner of the building”, which is located in “a cheerful healthy spot” (American Notes, ch. 3). In the novelist’s view, the favourable conditions under which the classes are conducted undoubtedly contribute to the institution’s educational success.

Similar sentiments are echoed during Dickens’s visit to one of the mills in the nearby manufacturing town of Lowell. He observes that the young female employees were “all well dressed: and that phrase necessarily includes extreme cleanliness” (American Notes, ch. 4). In contrast to their “moping, slatternly, degraded, dull reverse” in English industrial towns, the Lowell workers were “healthy in appearance, many of them remarkably so, and had the manners and deportment of young women: not of degraded brutes of burden” (American Notes, ch. 4). Dickens also notes the presence of washing facilities in the rooms where the women worked, as well as the general tidiness of the mill: “In the windows … there were green plants, which were trained to shade the glass; in all, there was as much fresh air, cleanliness, and comfort, as the nature of the occupation would possibly admit of” (American Notes, ch. 4). It is not surprising, then, that the mill workers found both the energy and the inclination for intellectual pursuits and amusements—such as subscribing to circulating libraries or writing and publishing their own periodical, The Lowell Offering—despite a twelve-hour workday (American Notes, ch. 4).

Works Cited

Dickens, Charles. American Notes for General Circulation, edited by Patricia Ingham, Penguin Books, 2001.

—. A Christmas Carol and Other Christmas Books, edited by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, OUP, 2008.

—. The Letters of Charles Dickens, edited by Madeline House and others, Pilgrim Edition, 12 vols, The Clarendon Press, 1965–2002.

Images

Figure 1. John Leech, “Ignorance and Want”, 1843, scanned by Philip V. Allingham. https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/carol/6.html

Figure 2. Ragged School Rhymes, 1851. https://archive.org/details/raggedschoolrhy00maclgoog/page/n6/mode/2up