text by Paweł Rutkowski

At the turn of the 18th century, what could be called the London culture of display accelerated its growth and became a truly significant part of everyday social life. Going out and seeing things that were considered interesting became a fashionable pastime, considered so attractive that more and more people were willing to spend their time and money in this way. Spectators could visit art galleries, cabinets of curiosities, private collections and public museums (the British Museum opened in 1751), but access to them was never as free and unrestricted as their visitors would have liked. London’s uniqueness, however, was that it offered a range of exhibition venues – the city’s response to the new fashion – that were perhaps less respectable, but certainly more accessible and affordable. These truly public venues were streets, fairs, inns, taverns and, not least, coffee houses. One of the most famous and popular of these was Don Saltero’s coffee house. Don Saltero – or, to use his real (and simple) name, James Salter – was a unique London character and entrepreneur. By trade, he was a barber and tooth-drawer who set up a barber’s shop at 18 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, around 1695.

The place, however, was soon transformed into a coffee house. In 18th century London owners of such establishments had to compete with many rivals to attract as many customers as possible. James Salter’s business strategy was to use his connections to turn his coffeeshop into a … museum. It should be noted that Salter once was the valet and travelling companion of Sir Hans Sloane, the naturalist and collector of natural curiosities (his collection was to become the core of the British Museum). He kept in touch with his former master (and his colleagues), who visited Don Saltero’s and even donated exhibits. The coffee house became a popular venue described and half-jokingly advertised in the press (most famously by Richard Steele in The Tatler, no. 34, 1709).

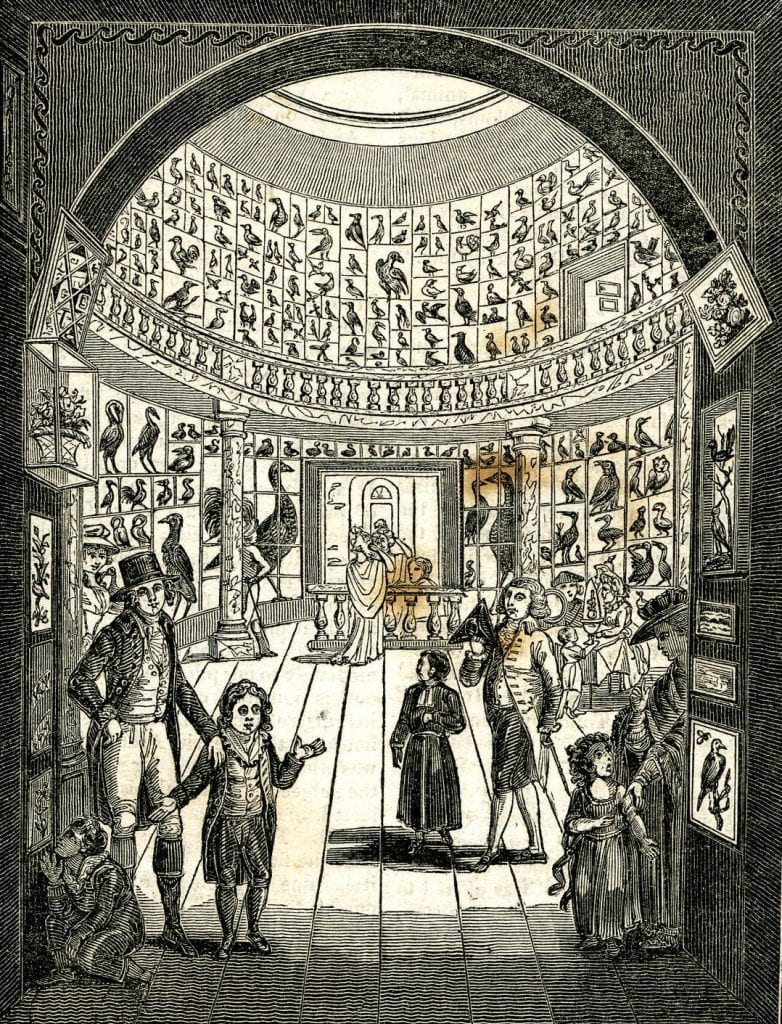

Undoubtedly, the most important thing was the extraordinary collection of objects that Don Saltero had amassed in order to attract his customers (another form of enticement was to be shaved or have your toothache removed free of charge…). To be sure, Saltero’s approach to his business was professional and systematic. He arranged and displayed objects in glass cases, and larger exhibits were mounted on the walls and ceiling or placed in the staircase.

To further satisfy his customers, Salter also printed A Catalogue of the Rarities to be seen at Don Saltero’s Coffee-House in Chelsea, which were sold (for 2 pence) so that their owners could walk freely about the place, identifying and admiring the objects on display.

The catalogues – issued throughout the 18th century up to 1795 – show how numerous and varied Don Saltero’s collectibles were. According to the 1785 edition, for instance, the collection contained as many as 731 things and included: “the model of our Blessed Saviour’s sepulchre at Jerusalem”, “a curious sprig of white coral”, “a curious sword set with polished steel, presented by the king of Lilliput to capt. Gulliver”, “an enamel of king Charles II. in miniature”, “the four Evangelists heads, carved on a cherry-stone”, “a petrified snake”, “an elf’s arrow”, “Bezoar stone from the stomach of a deer”, “a very large tooth of a shark, petrified”, “letters in the Malabar language”, “an alligator’s egg”, “a locust in spirits”, “an Indian pipe of peace, called by the natives the Calamet”, “instruments for scratching the Chinese ladies backs”, “Mary queen of Scots pincushion”, “Queen Elizabeth’s stirrup”, “two poisoned daggers of great antiquity”, and so on, and so forth…

In Salter’s museum, which was more of a cabinet of curiosities, you could find literally anything – from historical artefacts to natural specimens – anything that might cause wonder or at least curiosity. Don Saltero’s remained a museum – after Salter’s death run by his daughter – up to 1799, when the house, together with all its “rarities”, was sold at auction and turned back into an ordinary tavern. The sale of all the exhibits brought in an income of just £50, which symbolically showed that the era of similar venues was a thing of the past.