text by Dorota Osińska

*The blog entry is based on my PhD dissertation Reclaiming Hellenic Myth: Revisions of Mythological Heroines in 19th century British Poetry and Art

The intersection of Hellenism and womanhood was a powerful platform to debate roles and images of women in the Victorian era. Admittedly, Hellenism’s primarily men-oriented character would deter women from taking part in the classical discourse. As Dorothy Mermin argues, “women’s access to the classics was restricted in order to keep women out of the club, which was partly defined precisely by that exclusion” (51).

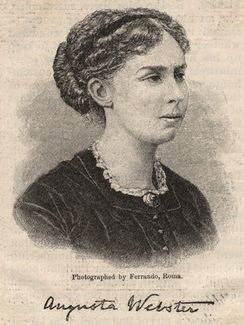

However, when we look at how women engaged with Hellenic writings in British literature, we may notice that their insight into classical tradition was not a sign of pure aesthetic excitement. Rather, it served as a practical framework to discuss intellectual, socio-political, and personal challenges connected with womanhood. For instance, Augusta Webster was an English poet, essayist and amateur classical translator (in 1868 she translated Euripides’s Medea). Her various dramatic monologues (“Circe” or “Medea in Athens”) contain subversive female characters of Greek mythology whom she represents through a very sympathetic eye, pointing out that the heroines’ marital and personal struggles cross the boundaries of time and place.

Similarly, in Middlemarch (1871), George Eliot demonstrated that women’s effort to acquire classical education was perceived either as a waste of time or an overwhelming experience. Dorothea Brooke’s observation of Ancient Rome illustrates a fascinating play between the emotional response to art and its learned appreciation. Eliot presents the encounter with the Ancient culture not as an entirely illuminating incident but rather as an alienating one. Although Dorothea longed to explore the ruins of Rome, the moment she sees them in flesh and blood, she feels “the weight of unintelligible Rome” (Eliot 161). Ultimately, Eliot’s character is emotionally and almost physically (“an electric shock”) crushed by history and perplexed by the long-standing heritage that she has stumbled upon.

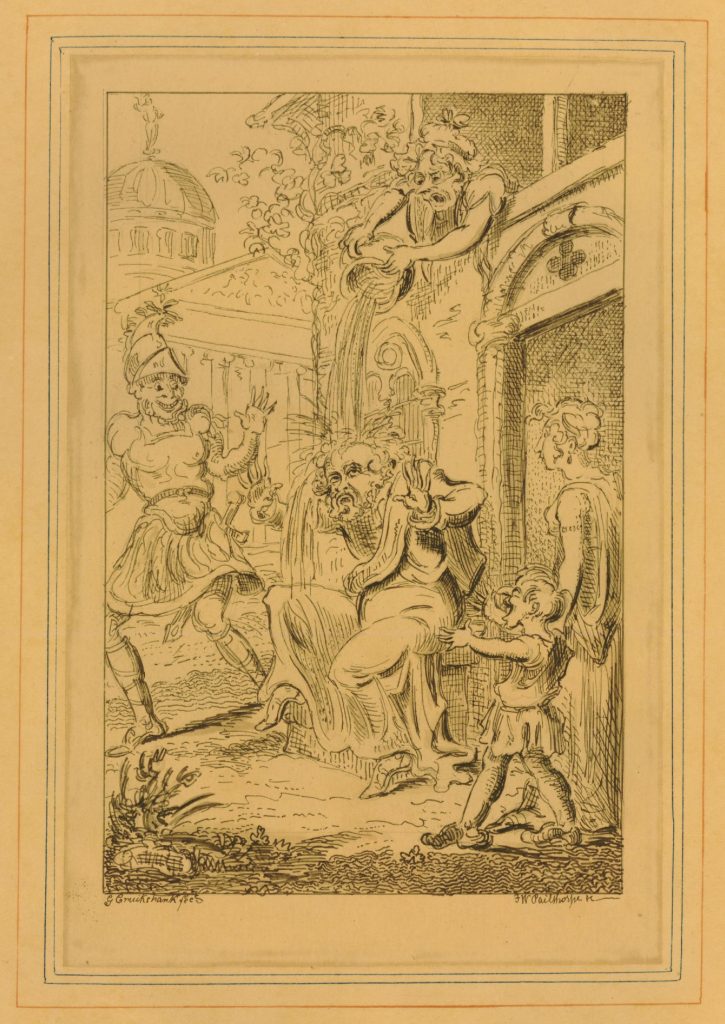

In a similar spirit, Amy Levy’s poem “Xantippe” (1881) addresses the problem of women’s hunger for knowledge and academic recognition. By transferring the Victorian issue of education into the Greek framework, Levy criticises Victorian society for discouraging women from academia and for perceiving these women as unwomanly and rebellious. Effectively, Levy’s dramatic monologue tells us the story of women who initially believed that their intellectual pursuits would be supported by their husbands but ultimately disapproved of that.

All in all, women writers’ reinterpretations of classical heroines reveal how mythology could be reused in the context of the Victorian period. Usually, these rewritings dealt with the concerns of inclusion and exclusion, higher education or academic recognition. Yet, they also touched upon more personal (and paradoxically universal) topics: complex relationships between men and women, an intriguing dynamic in female communities, and the individual quest for self-definition.

Works Cited

Eliot, George. Middlemarch [1871]. Wordsworth Classics, 1994.

Mermin, Dorothy. Godiva’s Ride: Women of Letters in England, 1830–1880. Indiana University Press, 1993.

Images

Augusta Webster: National Portrait Gallery, London https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw65446/Augusta-Webster-ne-Davies

George Eliot: George Eliot Archive, edited by Beverley Park Rilett. https://georgeeliotarchive.org/items/show/2413

Xantippe: The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1871-0429-730