text by Dorota Babilas

The University of Dundee will be hosting The Year of Gothic Women conference on 29-31 August. One of the QAQV members, Dorota Babilas, will be there with “Musicians, Models, and Other Monsters: Gothic Divas in George Du Maurier’s Trilby, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and Gaston Leroux’s Le Fantȏme de l’Opéra.”

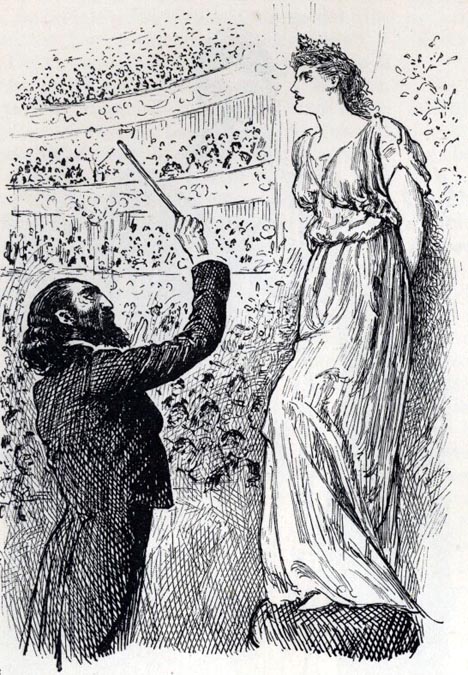

In the words of French philosopher Catherine Clément, opera as a genre has been involved from its beginnings with the “undoing of women,” almost ritualistically displaying their sexuality and (usually violent) deaths. The diva, as the main focus of this treatment – both the object of adoration as an artist, and a symbolic sacrifice as a character she performs – has been the “holy monster” of the stage, the feral femme fatale. George Du Maurier’s half-forgotten protagonist Trilby (1894) has been a haunting presence on the margins of Gothic literature canon. As a “fallen” Parisian painters’ model turned into the star of opera by means of hypnosis by an overpowering impresario Svengali, Trilby O’Ferral situates herself between the images of Victorian monstrous prima donnas – George Eliot’s The Alcharisi of Daniel Deronda (1876) and the title heroine of Armgart (1878) – and the ambiguous Gothic women of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) and Gaston Leroux’s Le Fantȏme de l’Opéra (1910), which she (at least partially) inspired.

George Du Maurier was already a well-known illustrator for the satirical magazine Punch when he decided to try his hand in writing. Trilby was his second published novel, and unlike the first one, it struck a nerve with the reading public on both sides of the Atlantic, becoming one of the most successful late-Victorian best-sellers and inspiring a surprising range of commercial merchandise, the most lasting being perhaps the Trilby hat. Now it has been largely forgotten; the blatant anti-Semitism of making the villain stereotypically Jewish became problematic, as noted by George Orwell, after the Holocaust.

Still, the image of the Gothic diva continues to mesmerize (the practice of hypnotism is in itself an important trope in the novel). Susan Leonardi and Rebecca Pope in their book The Diva’s Mouth (1996) relate the prima donna’s vocal mastery to her power of inspiring in the listeners the same lunacy she carries within herself. Yet, if divas are to be understood as dangerous sirens, their voices prove most fatal to themselves. The divine fire in their throats burns them out, fed by the “unsexing” Luciferian pride, which makes them transcend the socially proscribed female roles and speak out in the Temple of Art – a problem central to many Gothic narratives, especially the ones rooted in Victorianism.

Further Reading:

Univeristy of Dundee, The Year of the Gothic Women Conference: https://gothicwomenproject.wordpress.com/conference-the-year-of-gothic-women/

Emma Garman, “Trilby, the Novel that Gave us ‘Svengali’,” Longreads, February 16, 2017: https://longreads.com/2017/02/16/the-novel-that-gave-us-svengali/

Brian Benoit, “Trilbymania: How a Victorian Novel Became a Viral Sensation in 19-Century America,” Readex Blog, September 29, 2020: https://www.readex.com/blog/trilbymania-how-victorian-novel-became-viral-sensation-19th-century-america

Maxime Leroy, “Looking for Echo in George Du Maurier’s Trilby: An Intermedial Perspective,” Polysemes, 20.2018: https://journals.openedition.org/polysemes/4234

George Orwell, “As I Please,” Tribune, December 6, 1946: http://www.orwelltoday.com/orwellsemitismtrilby.shtml

The Victorian Web, George Du Maurier’s original illustrations for Trilby: https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/dumaurier/trilby/index.html

Original illustrations by George Du Maurier:

https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/dumaurier/trilby/27.html https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/dumaurier/trilby/84.html