text by Paweł Rutkowski

The Royal Collection contains an extraordinary picture of Christ as “Salvator Mundi”, a copy from 1798 of the painting by the Baroque Italian artist Carlo Dolci. What makes this replica unusual is that it was not painted but… embroidered.

The artist who produced it was Mary Linwood (1755-1845), who was undoubtedly the most famous English embroideress at the turn of the 19th century. In The Art of Needle-Work, a history of embroidery “from the earliest ages” published in 1840, Miss Linwood and her work represented “the triumph of modern art in needlework” (Stone and Wilton 395); she was the only embroiderer mentioned in the concluding chapter of the book).

Mary Linwood learned her extraordinary needlework skills from her mother at an early age, and she started creating more complex pieces as a teenager. She used a style of embroidery called “needle-painting”, known in England since the end of the Middle Ages and particularly popular in the 18th century. The tonal smoothness, shading and rough texture of this type of needlework (made with fine worsted woollen threads densely packed together) imitated brushstrokes and was therefore ideal for what Linwood specialized in: making full-scale textile copies of well-known paintings by artists such as Sir Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, George Morland, George Stubbs, Salvator Rosa, Guido Reni and others.

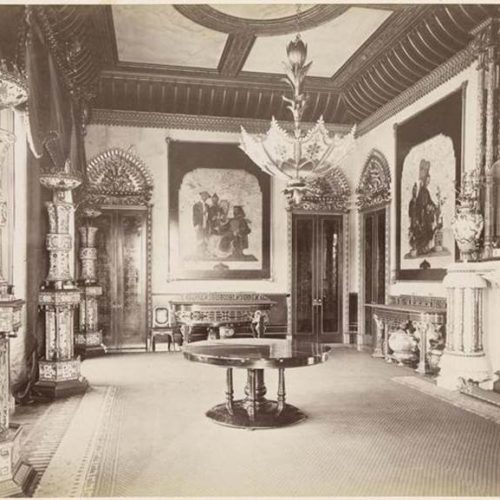

Her work was recognised and appreciated: in 1776, she was allowed to exhibit her embroidered pictures at the Society of Artists in London. In 1787, she met with Queen Charlotte, who was impressed by her artistic output. This led to her first public exhibition on Oxford Street in London that same year. In 1809, she finally opened her own permanent gallery in Leicester Square, where she displayed about sixty of her textile works. This was really a revolutionary step in the exhibition business in England: it was the first gallery owned by a woman artist and her works were presented in a professional and attractive manner. It was a posh place indeed – the main hall being adorned with “scarlet cloth, satin and silver” – and, moreover, it was also the first public show lit by gas lamps, meaning it could be visited by the audience even in the evening. Mary Linwood’s gallery thus became an important and fashionable destination on London’s cultural map and remained so for decades until her death in 1845.

Famously, she was once offered 3,000 guineas for the aforementioned Salvator Mundi, which was displayed in her gallery, but she declined (she eventually decided to bequeath this embroidery to Queen Victoria, which is why it is now part of the Royal Collection). Generally, she never sold her works as her objective was to keep her collection together. It seems that she treated her gallery as a kind of educational tool. After all, as well as being an artist, she was also an educator – for 50 years she was the headmistress of a girls’ boarding school in Leicester (founded by her mother). Her intention seems to have been to demonstrate and promote art, particularly British art, which preoccupied her (interestingly, John Constable’s first commission was to paint the background in one of Linwood’s works).

After Mary Linwood’s death, interest in her art and gallery declined. It proved impossible to keep her collection intact. At Christie’s auction, her pictures were sold to individual buyers and the overall profit was only £300… This was partly because artistic tastes had changed, and traditional needle painting was no longer in vogue. Among the Victorians, a new fashion, or even craze, emerged for an embroidery technique called “Berlin wool work”, which was simpler to practise and used brighter colours. Unfortunately, all this affected Mary Linwood’s posthumous reputation: she was increasingly dismissed as a mere copyist and imitator, which seems rather unfair. Apart from making copies of paintings, she also embroidered her own original works, such as The Judgment of Cain from 1830 – the last piece she completed in her 70s, before her impaired eyesight prevented her from creating any more – or the 1825 portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte (whom she met in person in 1803).

Besides, it should be remembered that her work – and embroidery in general – should be analysed not only in terms of imitation but also adaptation. Translating from one medium (painting) to another (embroidery) definitely requires creativity and interpretative skills. For example, a simple comparison of George Stubbs’ Tigress with Mary Linwood’s 1798 version of it reveals that her work was not a slavish imitation of the original but rather an interpretation resulting from the embroideress’s imagination and the technical requirements of her art.

Fortunately, renewed interest in the 18th-century women artists has recently revived the memory of Mary Linwood and her creative work. In 2023, Heidi A. Strobel published The Art of Mary Linwood. Embroidery, Installation, and Entrepreneurship in Britain, 1787-1845, the first scholarly book on Mary Linwood and catalogue of her work. Leicester Museum & Art Gallery has also recently organized a retrospective of her work (Event Details – Leicester Museums). Hopefully, there will more events like this as well as more relevant research – Mary Linwood certainly deserves more attention.

Works Cited

Desnoyres, Rosika. Pictorial Embroidery in England. A Critical History of Needlepainting and Berlin Work. London: Bloomsbury, 2019.

Hunter, Clare. Threads of Life. A History of the World Through the Eye of a Needle. New York: Abrams Press, 2019.

Stone, Elizabeth, and Wilton, Mary Margaret Stanley Egerton, Countess of. The Art of Needle-Work, From the Earliest Ages: Including Some Notices of the Ancient Historical Tapestries. London: H. Colburn, 1840.