Text by Paweł Rutkowski

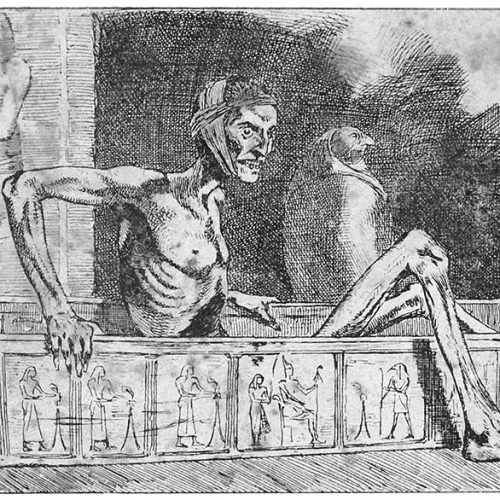

In 1712 Samuel Johnson was brought from Lichfield to London by his mother so that he could be touched by Queen Anne and thus healed. When he was later asked about the meeting with the queen, he vaguely recollected “a lady in diamonds and a long black hood”. Apart from that memory, he had also a tangible memento: a golden coin he had received from the royal and then kept till his death.

This early episode in Johnson’s life was part of the extraordinary story of Western kingship viewed as sacred and therefore endowed with (semi)miraculous powers. Traditionally, since the Middle Ages, the sign of a French or English monarch’s divine status had been his or her ability to heal scrofula – a disease of the neck lymph nodes – also known as “the king’s evil”.

Queen Anne, as a Stuart, endorsed the concept of kingship authorized directly by God – as well as the Royal Touch doctrine – and dutifully took part in ceremonies during which her subjects suffering from scrofula were brought to her. She touched them and distributed golden “touch-pieces”, valuable souvenirs and symbols of the royal care and healing power. The English touch-pieces were “angels” – golden coins (only then replaced by very similar medals) – with holes bored, which enabled their owners to wear them on ribbons or chains.

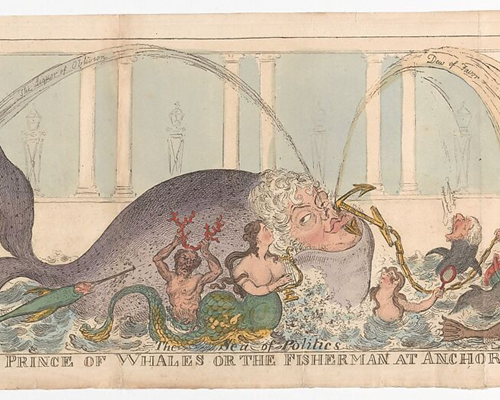

Interestingly, after 1688 – when King James II was deprived of the crown and had to flee to the continent – the Royal Touch became an instrument in the ideological war between the exiled Stuarts and the “usurping” Hanoverian kings. James II and his successors – his son James III and grandson Charles III – enthusiastically practiced the healing of the king’s evil (the Stuart archives show that they distributed thousands of touch-pieces, even though they were no longer golden: silver ones had to suffice as a result of the exiled Stuarts’ perennial financial problems…). In this way they wanted to prove to the world that they were still legitimate kings of Britain and, at the same time, to distinguish themselves from the Protestant Hanoverians, who adamantly refused to perform as healers: for them the Royal Touch was merely a nonsensical Popish superstition.

It means that the century-long tradition of touching for the king’s evil ceased in Britain in 1714, with Queen Anne’s death. However, it managed to survive in memories of people like Samuel Johnson as well as in numerous touch-pieces, which first served as keepsakes for their first owners, and then, with time, became historical objects valuable for antiquaries, collectors and museums.

Illustrations: