Text by Dorota Babilas on the Hammer studio’s The Phantom of the Opera (1962) based on her chapter from Dark Recesses in the House of Hammer

Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris (Eds) Peter Lang, 2022

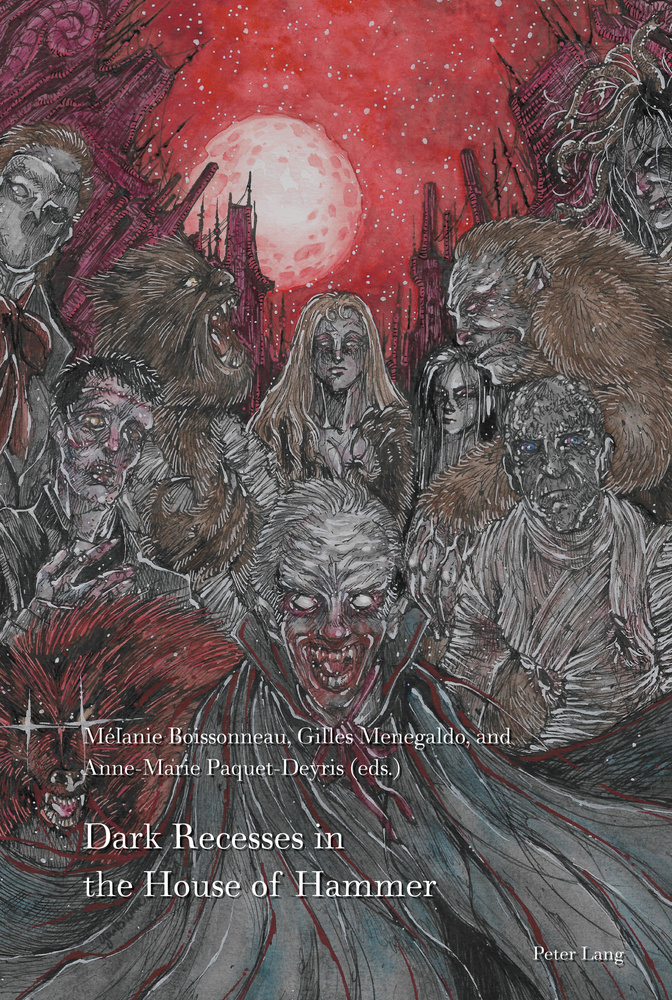

A new collection of essays (Peter Lang, 2022) edited by distinguished film and literature scholars, Gilles Menegaldo, Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris, and Mélanie Boissonneau, explores the legacy of the Hammer studio. The independent studio made its name through a distinctive style of horror movies, which, according to the volume’s editors, “brought back the great mythical figures inspired from British literature as well as French and European folklore (Dracula, Frankenstein, the Werewolf, the Phantom of the Opera, etc.).” The essays address contemporary re-evaluations of Hammer horrors in terms of aesthetics, gender, genre, and post-colonialism, as well as try to come to terms with the studio’s peculiar balance between classicism and inventiveness.

My chapter looks at Hammer’s take on The Phantom of the Opera (1962, starring Herbert Lom), focusing on the ways in which the first British adaptation of Gaston Leroux’s novel (and remake of Universal’s silent movie of 1925) tries to reframe the story of the alleged haunting of an opera house into distinctively Victorian aesthetics.

Arguably one of the least terrifying among Hammer horrors, Terence Fisher’s The Phantom of the Opera has surprisingly little in common with the classic French thriller of 1910 that it claims to be adapting for the screen. Neither is this a remake of the famous Lon Chaney vehicle of 1925 which, despite its flaws, has remained the most faithful screen adaptation of Gaston Leroux’s novel to date. In effect, what seems to be the major source of inspiration for Fisher is the heavily sanitized 1943 Hollywood version of The Phantom starring Claude Rains – offering musical melodrama in place of the Gothic macabre. Whatever horror is left in the Hammer Phantom, it is not in the (otherwise good) performances of the cast, but in the foreboding atmosphere of foggy, gas-lit streets created by the cinematography of Arthur Grant, the studio’s regular collaborator. Interestingly, the Hammer Phantom relocates the story of the haunted Opera House from belle epoque Paris to Victorian London. It is an important step in what turned out to be nearly complete Anglicization of Leroux’s tale and its implications for the decades to come. Additionally, many central elements of the plot were changed, including turning Erik, Leroux’s nearly preternaturally talented super-villain, into a modest and unassuming English music teacher, Professor Petrie, whose life opus gets stolen by a greedy aristocrat. This transformation of the dark and menacing original Phantom into a tragic hero, more sympathetic and memorable than the nominal romantic lead, was to prove a lasting, if perhaps unintentional, legacy of the Hammer version.

Other contributions concern i.a. the intermediality of Frankenstein, the political background of the revamped Dracula film series, and colonial horrors in Hammer movies.

The book is available at the Institute of English Studies library.